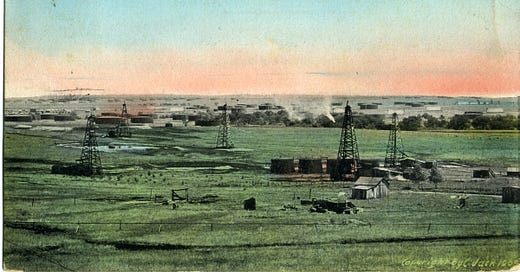

A postcard of the Glenn Pool in half tone color in 1909. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Download a PDF version of this article for the classroom

Edith Durant was only 6 years old on Nov. 22, 1905, when a geyser of black gold arced into the sky just south of Tulsa. The land allotment of a Creek woman named Ida Glenn was bubbling with enough oil to fill 75 barrels per day, and young Edith’s land was just southwest of Ida’s. Soon towering derricks would stretch across the open prairies for acres, and then for miles, as oil and money and power surged out of the earth and into the small frontier town nearby. The sea of oil would come to be known as the Glenn Pool. But approximately a quarter of the 15,000 acres surrounding Ida Glenn’s allotment were owned by black Creek citizens like Edith, who was too young to know she was about to become unfathomably, dangerously rich.

Oklahoma district judges assigned legal guardians to young freedmen and Native Americans such as Edith, ostensibly as a way to protect them from financial predators. Guardians had wide latitude to negotiate leases with oil companies that wanted to drill on freedmen land, buy houses for their wards, or sell freedmen’s oil-rich property to the highest bidder. Though parents sometimes acted as guardians, often the role was filled by white lawyers who had turned guardianship into a lucrative profession. It was not unheard of for a single guardian to have dozens of wards.

During the heyday of the Glenn Pool, Edith’s guardian was a banker named Bates Burnett, who lived in a nearby town called Sapulpa. While Edith was growing up in the small community of Boynton about an hour away, it was Burnett’s job to look out for her financial interest. Instead, according to newspaper reports, he loaned $40,000 of Edith’s money to his brother to build a hotel in Sapulpa, then loaned another $10,000 to an investment company where his brother served as president. In 1911, a judge ordered Burnett to pay $48,000 back to Edith’s estate, or about $1.3 million in today’s dollars. He resigned shortly thereafter.

Like the grafter Cass Bradley I discussed in my last newsletter, Burnett faced few long-term consequences for his duplicity. The same year his scheme was uncovered, he built a decadent mansion in Sapulpa that featured Tiffany chandeliers and hand-painted ceilings by European artists. Contemporary news articles refer to Burnett as a “prominent part” of the opening of the Glen Pool. His mansion is a “beloved” venue for genteel lunches doused in plantation-era nostalgia. The tactics he used to earn his wealth have largely been forgotten.

Though Edith’s case received wide media attention, treachery in the oil fields near Tulsa took many forms. A freedman named Zeke Moore was in prison in Kansas when the frenzy over the Glenn Pool began. Three men--I.N. Ury, Fred Sawyer, and G.R. McCullough--attempted to get Moore to sell off his land in exchange for $1,200 and a possible pardon, without telling Moore that the property was rich with oil. A judge later ruled the deal fraudulent, calling it sufficient ‘“to shock the conscience of any man.”

In Tulsa, the treatment of freedmen in these cases sparked widespread outrage in the black community. Though freedmen and “state Negroes” from the Deep South had long been at odds, they developed a tighter bond as both groups risked being ground into poverty by an economic system designed to favor whites. “The white man has done everything possible in Oklahoma to humiliate the Negro and to retard him in his progress,” wrote A.J. Smitherman, the fiery editor of the Tulsa Star, one of Oklahoma’s most prominent black newspapers. “We do not believe it is fair and just to the race to put white men in control of most of the Negro wealth in the state."

Smitherman’s column was picked up by the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis and helped bring guardianship fraud to national prominence. In 1915 the editor formed the Negro Guardianship League, an organization that advocated for black lawyers to watch over the affairs of black freedmen.

Racial solidarity wasn’t always a solution to the problem of graft--a young boy named Robert H.P. Watson, who lived in the Greenwood district, lost much of his oil wealth to his gambling stepfather until his mother petitioned for a new guardian. Smitherman acknowledged such cases, blaming “shiftless Negroes [who] will make themselves tools for the white man in this knaver work.” But he was a fierce advocate for letting black people work through the good and bad of guardianship arrangements themselves. “We are opposed to the white man serving as guardians of Negro children for the same reason that he is opposed to Negroes serving as guardians of his. He has separated us from him in everything else, why not in this?”

Black people who maintained their wealth in Oklahoma did so against a current of graft and guile meant to impoverish them at every step. For Durant, though she was reportedly worth more than $100,000 when she came of age in 1917, she ultimately had to file a petition against a later guardian who wanted her declared an incompetent adult in order to retain control of her money. Black wealth in Oklahoma was unusually prevalent, but holding onto it was a constant, exhausting struggle.

Thank you for reading. To learn more about the origins of Greenwood, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the community’s astonishing rebirth, check out my narrative nonfiction book Built From the Fire. The book was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and the Washington Post, and it has been named a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. Buy Built From the Fire on Amazon, Bookshop, or at your local bookseller.

Want to read more stories about neglected black history? Subscribe to Run It Back and receive articles just like this one in your inbox every other week.

Sources

“Bates Burnett Case for Trial.” Muskogee Daily Phoenix. Nov. 19 1911.

Bolden, Tonya. Searching for Sara Rector: The Richest Black Girl in America.

Hastain, E. Hastain’s Township Plats of the Creek Nation. Muskogee, OK: Model Publishing Co., 1910.

“He Loaned $40,000 on $30,000 Hotel?” Tulsa World. Oct. 7 1911.

“The Poorest Lands Make the Richest Negroes in Oklahoma.” Muskogee Times-Democrat. March 31 1917.

Robert H.P. Watson Guardianship Records. Tulsa County Courthouse.

Smitherman, A.J. “Negro Minors and the County Courts.” Tulsa Star. July 24 1915.

“Undue Influence to Secure Trust Deed Is Charged.” Muskogee Times-Democrat. June 20 1918.

Vandewater, Bob. “Glenn Pool ‘Blew In’ State’s Oil History.” The Oklahoman. April 24 1994.

“What the Decision in the Zeke More Case Really Means.” Tulsa Democrat. July 14 1909.

Weaver, Bobby. “Glenn Pool Field.” Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.