The Story of Black Wall Street #006: The Messages Hidden in Maps

How an obscure collection of urban maps can reveal more than pages and pages of text

Welcome to the sixth edition of Run It Back, my biweekly newsletter about neglected black history. For the foreseeable future the newsletter will be focused on Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, which I’m currently writing a book about for Random House.

I often struggle to visualize the past. Many of my days are spent poring over old newspaper articles, land deeds, and academic dissertations--mountains of text that are rarely punctuated by photographs of the places being described. Visiting a historical location myself helps, but time and human activity have a way of ravaging landscapes. This is especially true of black spaces, which are often under threat from outside forces. The transformation of black-owned property can be a spectacle of violence, like the race massacre, or a silent injustice, like the fraudulent land dispossession suffered by black freedmen. Either way, the world that existed before a dramatic disruption is almost unknowable to modern eyes.

So I was very thankful early in my book research to stumble upon Sanborn maps, a series of documents that illustrate, in surprisingly granular detail, the world as it once was.

The Sanborn Map and Publishing Company, founded in 1867, created detailed maps of more than 12,000 American cities and towns over the course of a century. Its customers were fire insurance companies, who needed detailed information about the design and building materials of urban structures in order to set premiums. At its peak, Sanborn had a team of 300 surveyors who crisscrossed the country, carefully documenting the landscape of practically every city. These surveyors noted the layout of individual rooms, the presence of gas stoves or electrical wiring, and even the height of the rooftop eaves. Their notes were converted into brightly color-coded maps that somehow marry our modern obsession with Big Data with the handmade human craftmanship of a bygone era. As a relatively young person and a reformed tech reporter, it’s humbling an eye-opening to see how people made sense of the world before computers, in ways that are often more informative than what our modern gadgets offer (Google Maps, for example, can’t tell me how tall every building in Tulsa is). Here’s a 1911 map of Greenwood Avenue, the street in Tulsa now commonly known as Black Wall Street:

The corner of Greenwood and North 1st Street (now Archer Street) at the bottom of the map was the epicenter of black commerce in Tulsa and often referred to as “Deep Greenwood.” At a glance, the map reveals that the street had a two-story movie theater, a cobbler, a meat market, a skating rink, and multiple pool halls. Pink buildings are made of brick, while the yellow ones are wooden frame structures--the prevalence of pink indicates that the area was already seeing robust development a decade before the 1921 massacre. This kind of map is extremely valuable because it provides a sense of place for the figures whose lives I hope to animate with my work.

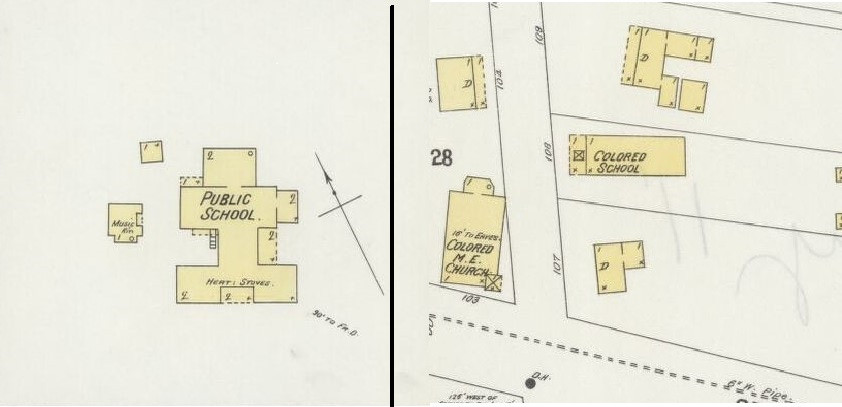

Sanborn maps are also useful for visualizing inequality. Before digging up the maps for Tulsa, I reviewed the ones for Water Valley, Mississippi a tiny railroad town near Oxford. One of the prominent black Tulsa families I’m writing about hails from Water Valley, and they left the Deep South seeking to escape the boundaries of Jim Crow that had closed in around them in the small town. I’ve now read several books and academic papers about disparities in education in post-Reconstruction Mississippi--school systems spent $8 educating each white student compared to $1 for each black one, and white teachers in Water Valley earned more than double what their black counterparts made. But the most vivid depiction systemic racism came from simply comparing the black school and the white school in Water Valley on the Sanborn Map:

In 1898, Water Valley’s white public school (pictured on the left) was a two-story structure with multiple rooms, stove heating, and a separate music room facility. The “colored school” (on the right) appears to have been one large room for all instruction devoid of any heat. In a later 1910 map, the contrast was even more stark--the white school had grown to three stories with steam heating and electric lights. Black kids were still being taught in the same big room, and the maps don’t denote any addition of electricity or heat (though a small annex was added next to the main schoolhouse). The Tulsa family has passed down an oral history that they left Water Valley seeking better educational opportunities--the data on display in the Sanborn maps makes that desire tangible.

Of course, the maps themselves are often bound by the same discriminatory forces that have long rendered black spaces invisible. In many cases the maps cover a city’s bustling downtown and its white neighborhoods but don’t reach far into black communities. In Tulsa, early Sanborn maps only depict the portion of Greenwood closest to downtown; much of the 35-square-block neighborhood wasn’t surveyed until 1915. Similarly, in Water Valley, local historians have told me about a black business district northeast of downtown, where records show the Tulsa family I’m researching owned property. But this area was never depicted on a Sanborn map, and the courthouse clerk told me business filings from that era were destroyed in a fire. A black business district that likely existed in the same era as Black Wall Street has been totally wiped from record, and nearly wiped from historical memory.

Still, the Sanborn maps are a valuable resource that more folks should utilize, whether you’re a journalist, a historian, or just a person curious about your hometown’s history. The Library of Congress has a massive archive of 700,000 pages of maps, some of which have been digitized. Chances are your local library also has the maps for your community on file. I encourage everyone to dive into this resource to get a clearer picture of the oft-obscured past.

If you found this email informative or enlightening, feel free to share it on social media.

Also consider forwarding to a friend. If you are that friend, consider subscribing below. And if you you have comments, critiques, or tips that may help with my research, just reply directly to this email. I’ll be back with more reporting from Tulsa in two weeks.

Sources:

“Biennial Report and Recommendations of the State Superintendent of Public Education to the Legislature of Mississippi for the Scholastic Years 1911-12 and 1912-13.” Brandon Printing Company. Pg. 257.

Bolton, Charles. The Hardest Deal of All: The Battle Over School Integration in Mississippi, 1870-1980. University Press of Mississippi. Pg. 21.

Ristow, Walter. “Introduction to the Collection.” Library of Congress.