The Story of Black Wall Street #008: Origin Stories

It's difficult to prove that some of the narratives surrounding Greenwood's early days ever occurred. How do they contribute to our understanding of history?

The story of Black Wall Street’s creation reads like a fable: a young black businessman named O.W. Gurley arrives in a frontier town, sees possibility in the miles of dusty plains that white people have ignored, and buys up 40 acres to sell exclusively to his brethren. He partners with another savvy black real estate man named J.B. Stradford to meticulously lay out streets, alleys, and housing plots for all their soon-to-be neighbors. They christen their new mecca Greenwood, after a mostly black community in Mississippi from which people are fleeing towards Oklahoma in order to escape Jim Crow violence.

Various versions of this narrative have crystallized into Greenwood’s assumed history. It can be found in books, news articles, and in debates on the floor of Congress. But the idea that Greenwood was a planned community, similar to the all-black towns like Boley and Langston that were emerging around Oklahoma at this time, doesn’t line up with the historical records that I’ve reviewed in recent months.

In the business district of Greenwood, black people appear to have purchased land when they could from white, Native American and eventually other black landowners, according to a review of hundreds of land deeds. Greenwood Avenue, the neighborhood’s signature street, already had its name when the city was initially laid out in 1902, which was before Gurley and Stradford arrived. Neither of the two men ever directly bought or sold more than a few pieces of property. This is all less narratively satisfying than the origin story, perhaps, but it illustrates that the world of early Greenwood was deeply shaped by the economic and racial dynamics of the era, rather than being safely cloistered off from them until the day of the massacre.

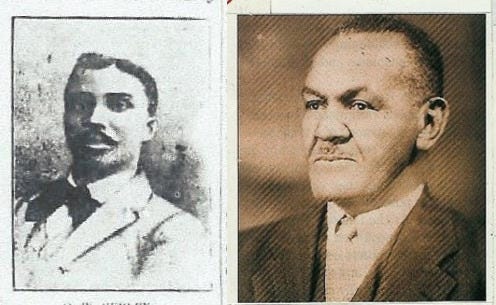

Two of Greenwood’s founders, O.W. Gurley (left) and J.B. Stradford (right)

Stradford and Gurley were “state Negroes,” black men from outside Oklahoma who arrived amidst the excitement of oil discoveries and impending statehood. But Greenwood’s origin story has to include the three groups that comprised the vast majority of Oklahoma’s population before it became a state: Native Americans, freedmen*, and white people. The land north of downtown Tulsa that would become Black Wall Street was originally owned by the Creek and Cherokee tribes. A small portion of Greenwood was part of the original Tulsa townsite and communally owned by the Creeks, while most of the neighborhood was Cherokee land that had been distributed to individual tribal members during the allotment process.

Much of the city of Tulsa--and indeed much of Oklahoma--had been formally owned by Native American tribes but settled and used by white people (and some “state Negroes”) who enforced their will through sheer numbers and the implicit backing of all levels of government. In Tulsa, when city leaders negotiated a sale of tribal lands with the Creek Nation, settlers who had already encroached on the land and “improved” it were given a steep discount. A white man named Elias Rambo bought an entire city block at the corner of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street for only $135 in 1902.

By 1906 almost all of the land that would comprise Greenwood had left Native American ownership. That was the year after Gurley arrived in Tulsa with his wife Emma from Perry, Oklahoma. The 39-year-old had raised cotton and operated a grocery store in Perry. He mixed the resourcefulness of a frontiersman (he is thought to have participated in the land run to claim his property in Perry) with the salesmanship of an aspiring business mogul (he liked bowties for his suits and pomade for his hair). Exactly what drew him to Tulsa isn’t clear. Muskogee was still the epicenter of black wealth in Indian Territory, due to its large population of land-owning freedmen. But the recent discovery of oil at the nearby Glenn Pool put Tulsa on the ascent.

Whatever the reason, the Gurleys opened a grocery store, rooming house, and event space called Gurley Hall all within a year and a half of arriving in Tulsa. Surrounding them were acres of open prairie and farmland. Some of the land was purchased in small chunks by black people in the ensuing years, but not in one calculated swoop. Gurley’s name was used for a district slightly north called the Gurley Hill Addition, and he may have been involved in promoting or facilitating transactions in that district, but he never owned a significant amount of property in it. The landholdings that made him rich were primarily farmlands he retained in Perry and Arkansas, according to the Tulsa Star.

J.B. Stradford’s first land purchase in Tulsa was a roughly half-acre lot he bought from a Cherokee woman for $450 a couple of blocks north of Gurley’s nascent businesses. Like Gurley, Stradford would go on to own several smaller properties. As a lawyer, he specialized in real estate loans and therefore was likely involved in setting up home mortgages for a number of black Tulsans. He served as president of the Oklahoma Realty and Investment Company, which sought to boost black wealth by pooling Greenwood residents’ resources on major land and infrastructure projects. But the specific transactions showing the fruits of Stradford’s labor have been difficult to track down.

An ad for J.B. Stradford’s real estate business in the Tulsa Star in 1914

I write all this not to diminish the efforts of these two men, which were numerous and important. Stradford converted that $450 plot of land into the luxurious Stradford hotel, valued at more than $65,000. He was also a fierce civil rights advocate who wrote eloquently on the subject in the local paper. Gurley was praised as a “pioneer citizen of Tulsa” in his own time and was a leader in Greenwood’s rebuilding effort. Of course their lives cannot be reduced to what remains in the historical record--a record that, in Tulsa’s case, is unusually limited because so many documents were destroyed by the fires of the massacre.

But I feel compelled to wrestle a bit in (semi) public with what I am finding to be a confounding aspect of historical writing. People need narratives in order to engage with and understand the events of the past. But the past was no more orderly than the world we live in today--it’s just that we pass down the narratives that have already been made sensible for consumption, and largely ignore the inscrutable, and sometimes conflicting data that emerges when you dig into a primary source like a book of land deeds.

I don’t yet know how to square the story (which isn’t reflected in the data) with the data (which cannot tell the whole story). I try to rely on information I can prove with verifiable documents, first-hand recollections from multiple sources, or my own eyes. So it may be that I just skip the 40-acre story in my final book and stick to what I can prove. And in delving into these men’s histories, I’ve discovered other unknown Greenwood stories that illustrate the success they’d achieved before 1921 (but I have to save some stuff for the book, right?). This is an interesting test case because I expect to come across many such hard-to-prove narratives as I retrace more aspects of Greenwood’s past.

*Re: freedmen, their exact role in Greenwood’s origins are still unclear to me. Some people have claimed that Greenwood was initially freedmen land, but reviewing the documents I found that not to be true (though areas both north and south in modern Tulsa were indeed owned by freedmen). I’m currently compiling a list of all the freedmen who lived in Tulsa in 1910 to get a better sense of the lives they lived and will expound on that in a later newsletter, or in the book.

If you found this email informative or enlightening, feel free to share it on social media.

Also consider forwarding to a friend. If you are that friend, consider subscribing below. And if you you have comments, critiques, or tips that may help with my research, just reply directly to this email. I’ll be back with more reporting from Tulsa in two weeks.

Sources

Biography of O.W. Gurley. Tulsa Star. Aug 19 1914

Goble, Danny. Tulsa!: Biography of the American City.

“Homeless Tulsa Riot Victims Tell Stories of Horror.” Chicago Defender. June 11 1921.

“K of P’s Ball!” Tulsa Guide. Sept 10 1906.

“Peoples Grocery Store.” The Tulsa Democrat. July 28 1905.

Tulsa Original Townsite Land Plat. Tulsa County Courthouse.

Tulsa County Courthouse land deeds

Tulsa Weekly Planet. Sept 5 1912.

“What the Colored Folks Are Doing in Perry.” The Western World. March 10 1904.