The Story of Black Wall Street: 'Get a Gun and Get Busy'

Local police and the National Guard failed to protect Greenwood from burning during the 1921 race massacre. In fact, their actions likely encouraged its destruction.

Download PDF version of this article

Laurel Buck, a 26-year-old white bricklayer, was at the county courthouse in downtown Tulsa when the first group of black men arrived in a car, armed with rifles and insisting to police officers they be allowed to protect Dick Rowland. There were as many as one thousand white people milling about the courthouse, self-described curious onlookers who were either there to see if Dick Rowland might be lynched, or planning to do the job themselves. The armed black men would have surprised, angered, and terrified this crowd all at once.

Sensing a volatile situation, Buck walked a block east to Main Street. Soon, he heard a gunshot, and then several more. The killing had begun. Buck made a beeline for the police station, where a crowd was forming outside. He hoped to be given a special commission and a gun to apprehend and potentially kill black people he felt were endangering whites. The police weren’t deputizing white citizens--not yet anyway--but what one officer told Buck portended how the rest of the night would devolve. “"They told me to get a gun and get busy,” he said later, “and try to get a nigger.”

---

The actions of white Tulsans during the massacre are extremely murky, due to a long-held conspiracy of silence. But the activities of law enforcement are surprisingly well documented. After black people themselves, it was the police that bore the brunt of the blame for what happened. This served twin purposes. It anonymized the thousands of individual people who participated in looting, arson, and murder in Greenwood. It also took attention away from local political and business leaders who tried to capitalize on the massacre after the fact and have long been suspected of playing some role in orchestrating it. I will explore the roles these other groups played in the massacre in later issues, but I’m starting with what we know the most about, which is the police’s abdication of its duty to protect and serve all of Tulsa’s citizens.

The first major failure by law enforcement was refusing to get Dick Rowland out of Tulsa. By 1921, race riots sparked by allegations of black violence were an American pastime, and police departments nationwide were well aware that the simplest way to cool tempers was to remove the black suspect from the equation. But Willard McCullough, the Tulsa County sheriff, insisted that Rowland would be safe in the courthouse jail, despite pleas by other officials to transport him elsewhere. McCullough did in fact manage to protect Rowland, turning away three white men who tried to enter the courthouse before the shooting started. But he also ignored the situation that was unraveling just outside the jail. From inside his barricaded fortress, McCullough opposed bringing in National Guard troops to help restore order, even after multiple people had been shot, downtown stores had been looted and crowds were gathering rather than receding as the night dragged on. "We believe we have the situation well in hand without further help,” he told a Tulsa World reporter from the jail.

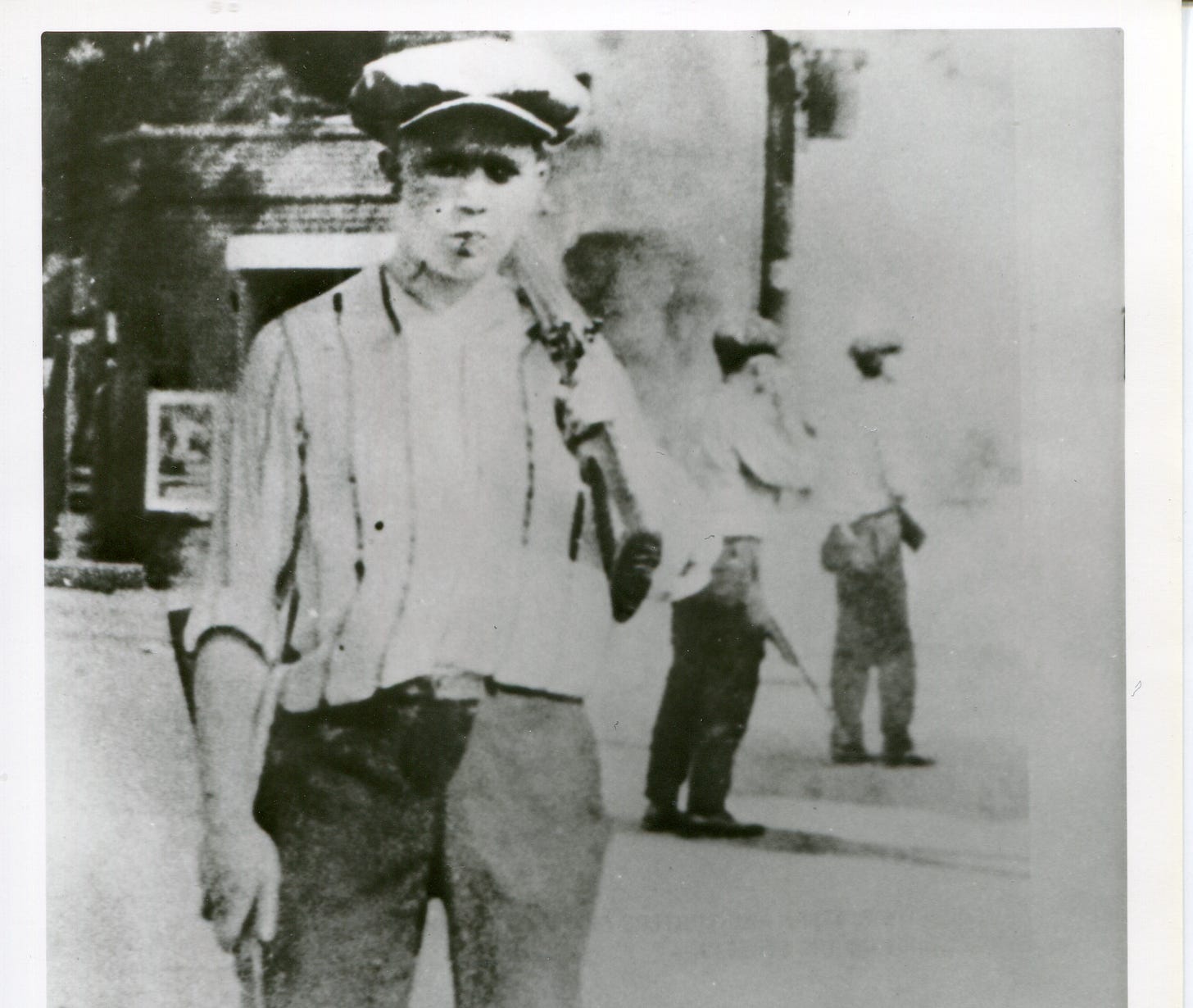

An armed white rioter stands on Greenwood Avenue in front of a building owned by John and Loula Williams. Photo courtesy Greenwood Cultural Center.

The sheriff eventually relented and signed an order requesting that Oklahoma’s governor send in the National Guard. But instead of trying to stop armed whites, who far outnumbered blacks and had already attempted to seize a downtown armory, the National Guard wasted time trying to put down an imaginary statewide black insurrection. Rumors indicated that a trainload of armed blacks were on the way from the nearby city of Muskogee, so the National Guard gathered up about a hundred white patrols and sent them to intercept the attackers south of town. The train ended up being a normal freight train; there were no black gunmen on it. Meanwhile, a military-grade machine gun, apparently brought over from Germany during World War, I was mounted on a truck by National Guard troops and placed on a hill overlooking Greenwood to intimidate blacks, some of whom fired upon white interlopers throughout the night (the gun was broken and brought out as a show of force, according to National Guard records). The directive to restore “order” in Tulsa, late as it came, ultimately meant disarming black people as quickly and aggressively as possible.

And yet the biggest transgression by law enforcement--and the one that I believe most directly connects to the wholesale destruction of Greenwood--was the decision to deputize hundreds of untrained and in many cases anonymous white men who, like Laurel Buck, were eager to “get a nigger” (Buck appears to have gone to the police for the deputization process started). After midnight on June 1, Charles Daley, a National Guard inspector and Tulsa police officer, encountered an armed mob of about 150 men near the police station. He divided them into small groups led by military veterans and ordered them to gather up all black people on the streets, using lethal force only “to protect life and if all other methods had failed.” The men were also ordered to round up black people living in servants’ quarters on white people’s property, as Daley suspected it was black people who were about to turn Tulsa to the ground.

J.M. Adkison, Tulsa’s police commissioner later estimated that 400 men were deputized on the night of the massacre. “'We were unable to limit the commissions to our choice,” he testified in court, admitting that many did not even have to provide their names to earn a commission. Adkison would later be identified as a member of the Ku Klux Klan; many Tulsa police officers were part of the organization in the 1920’s, though it was only in a nascent stage at the time of the massacre.

In written records and court testimony, police and National Guard leaders said they began the night with the intention of forming a protective ring around Greenwood to keep white intruders from entering. Instead, they spent much of their time in pitched skirmishes with armed blacks defending their neighborhood and empowered a group of reckless killers and arsonists to lay waste to the black community. The officers may well have been among these reckless invaders themselves--many black and white eye-witness accounts describe men in uniforms, but it’s often unclear whether these men are Tulsa police, National Guard members, or an amateur Tulsa militia known as the “Home Guard” which was comprised of World War I veterans.

What’s clear is that any compulsion to protect Greenwood or quell the violence was ultimately superseded at all ranks by a bone-deep paranoia white people harbored about the spectre of a black uprising. After leaving the police station on the night of the massacre, Laurel Buck got a gun from a hardware store and assigned himself a post guarding Third Street. He waited for the black invasion to arrive, but all he saw were hundreds of armed white people whipping themselves up into an excited fury. “There were people shooting out of cars,” he recalled later. “Shooting just to hear the gun go off."

Thank you for reading. To learn more about the origins of Greenwood, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the community’s astonishing rebirth, check out my narrative nonfiction book Built From the Fire. The book was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and the Washington Post. Buy Built From the Fire on Amazon, Bookshop, or at your local bookseller.

Want to read more stories about neglected black history? Subscribe to Run It Back and receive articles just like this one in your inbox every other week.

Sources

“Facts Disclosed in Talk With Newspaper Man.” St. Louis Dispatch. June 3 1921.

Krehbiel, Randy. Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre. 2019.

Ku Klux Klan Roster 1928-1932. University of Tulsa.

Laurel Buck Testimony District Court State of Oklahoma v. John A. Gustafson, Attorney General Civil Case No. 1062, Box 25, Record Group 1-2, Oklahoma Department of Libraries, Oklahoma City, OK

National Guard Report by Frank Van Voorhis. July 6 1921. Ruth Sigler Avery Collection (Series 1, Box 2). Oklahoma State University-Tulsa, Tulsa.

National Guard Report by Major C.W. Daley. July 6 1921. Ruth Sigler Avery Collection (Series 1, Box 2). Oklahoma State University-Tulsa, Tulsa.

Parrish, Mary Jones. Events of the Tulsa Disaster. 1922.

“Race War Rages for Hours After Outbreak at Courthouse.” Tulsa Morning Daily World. June 1 1921.