The Other Black Wall Streets

Greenwood was not the only prosperous black business district in the early 20th century--not by a longshot

Download PDF version of this article for the classroom

The week before Christmas in 1920, the leader of one of the nation’s largest black-owned businesses made his first scouting trip to Oklahoma. Aaron McDuffie Moore was the president of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, which surpassed $1 million in assets for the first time that year by selling health, accident, and life insurance policies to working class black people. Moore had helped nurture the firm from its inception in 1898, along with his co-founders John Merrick and C.C. Spaulding. Oklahoma was the company’s newest market, and the first that pushed beyond the typical boundaries of the South. By the time of Moore’s visit, North Carolina Mutual had already deployed insurance agents in Oklahoma City, Muskogee, and Tulsa. Like many black entrepreneurs from back east, Moore was surprised by the level of independence he found among the state’s black residents. “He had no idea that the race possessed such wealth in homes and property,” reported Oklahoma City’s black weekly newspaper, the Black Dispatch.

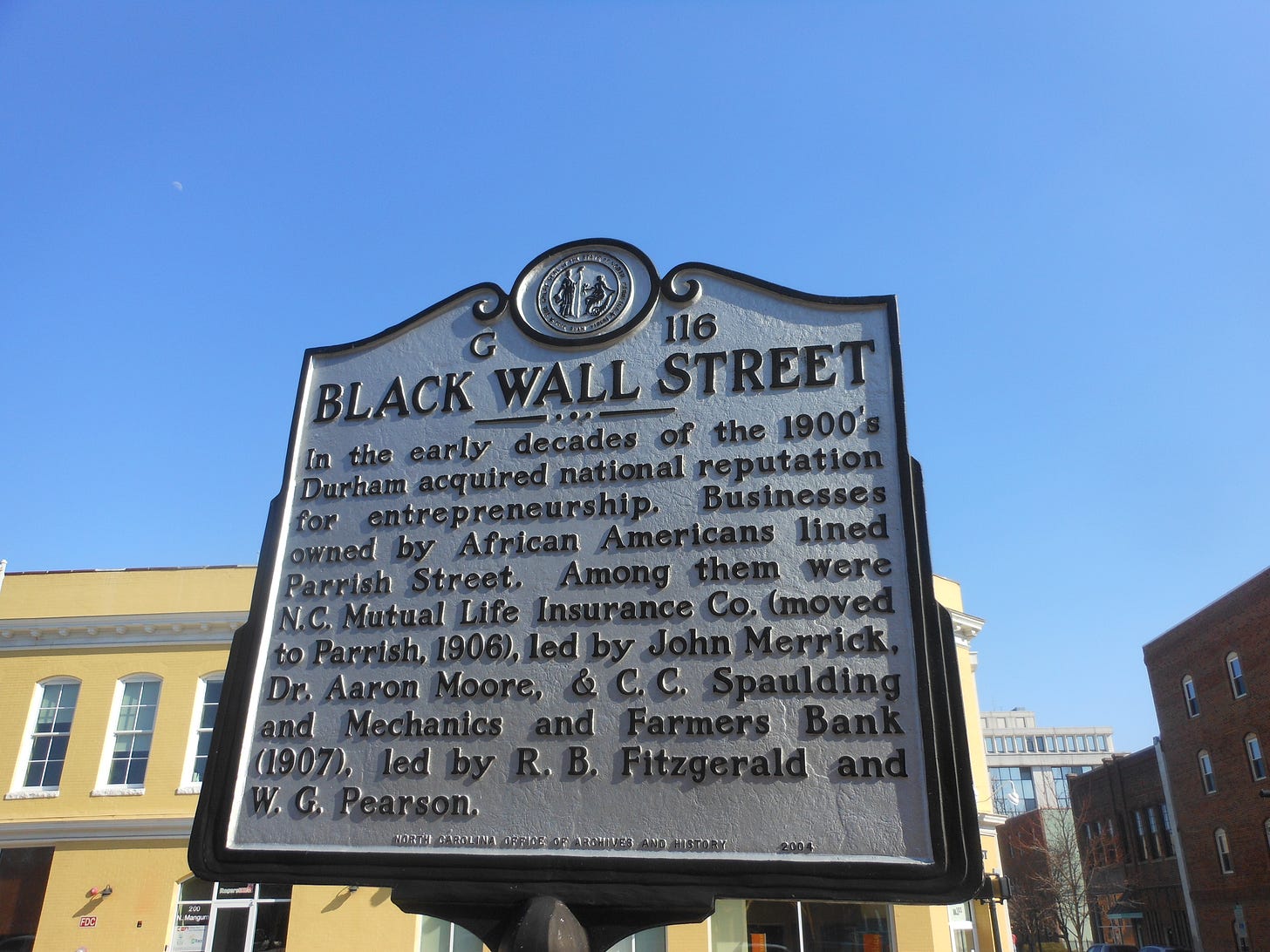

Moore was no stranger to black affluence. In his home of Durham, where North Carolina Mutual was headquartered, black entrepreneurs had also launched a mattress manufacturer, a cigar factory and a bank, among dozens of other businesses. Durham’s black community, known as Hayti, was praised by W.E.B. Du Bois as a leading example of black economic progress. In 1921 North Carolina Mutual even built a gleaming six-story new headquarters, the second-tallest building in all of Durham (company executives were careful not to make it the tallest to avoid angering white elites). So it’s no surprise that Durham, just like Greenwood, ultimately earned a now-iconic nickname: Black Wall Street.

A plaque denoting Durham, North Carolina’s “Black Wall Street.” Photo by Alexisrael.

The story of black America in the first half of the 20th Century is often focused on people’s desperate efforts to escape the South. Between 1916 and 1970, more than 6 million black people left the South for the North, the Midwest, or the West Coast. They incubated a world-shifting arts scene in Harlem, manned the assembly lines that built the modern economy in Detroit, and worked in shipyards during World War II in Los Angeles.

But Southern cities also swelled with incoming black migrants from rural areas during this period. The version of success black people carved out in places like places like Tulsa, Durham, and Richmond, Virginia, was markedly different than in the Great Migration cities. Many more black people in the South owned their own homes than in some major migration destinations--29 percent in North Carolina, 35 percent in Oklahoma, and 41 percent in Virginia, compared to 23 percent in Illinois, and only 8 percent in New York*. While black people were being recruited north to work in white men’s factories, foundries, and slaughterhouses, in Southern cities they were often recruited to work for black-owned businesses, or with the promise that they’d be able to go into business for themselves. North Carolina Mutual offered an appealing synthesis of both of these ideals, employing more than 1,100 people across the South, mostly sales agents who made money on hefty commissions when they sold insurance policies.

In Durham itself, North Carolina Mutual technically only employed about 60 people in 1920, but its reach was far greater. Aaron Moore and the other founders of the insurance company also organized North Carolina’s first black-owned bank, and through this entity played a key role in financing much of black enterprise throughout the region. These men also founded Durham’s first black hospital, its first black library and a black liberal arts college, North Carolina Central University. Most of these key institutions could be found either on Parrish Street, a Durham business district similar to Greenwood Avenue, or in the black residential neighborhood of Hayti located just to the south.

Moore and the other North Carolina Mutual founders espoused the ideology of Booker T. Washington, convinced that black people could chart a path toward freedom by climbing the economic ladder. But the fact that they channeled much of their wealth into building up black social and civic institutions earned them the admiration of W.E.B. Du Bois as well. And unlike in Tulsa, Durham’s white elite celebrated the North Carolina Mutual and its leaders, largely because they helped recruit middle-class blacks to the city, did not threaten core white-controlled industries such as tobacco, and remained largely apolitical (John Merrick, the company’s first president, was once a barber for Durham’s powerful Duke family). "When we began, we didn't have a thing,” co-founder C.C. Spaulding recalled later. “We had no money, no knowledge, But we had sense enough to put up a big front of respectability."

Richmond, Virginia also earned a reputation for black success, though its leaders were less reserved in their political advocacy. One particularly savvy businesswoman emerged as the leader of the black community’s economic rise. Maggie Walker, a former teacher and daughter of an enslaved woman, became an influential leader in a Richmond fraternal society. In 1901, she proposed that the society organize a bank, a newspaper, and a department store, all run by black people. It was the bank that would ultimately have the longest legacy, as Walker became the first black woman in the United States to charter a financial institution. “Let us put our money out at usury among ourselves, and reap the benefit ourselves,” she said in her 1901 speech. “Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.” Walker guided the St. Luke Penny Savings and Loan Bank, which eventually became the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company, through the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. The bank continued to operate under black ownership until 2005, more than a century after its founding.

Maggie Walker in 1913. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Walker’s businesses were located in the Richmond neighborhood of Jackson Ward, which also boasted a lively music and nightlife scene that helped it earn the nickname the “Harlem of the South.” Like Greenwood, Jackson Ward also had an irascible newspaper editor who had little patience for white people’s Jim Crow laws or black leaders’ effort to accommodate them. As the editor of the Richmond Planet, John Mitchell Jr. protested lynchings, segregated street cars, and the erection of a 14-foot-tall statue of Robert E. Lee. Maggie Walker was often at his side opposing these racist acts and policies--the two even ran together for public office on a Republican ticket in 1921.

Today, our understanding of communities like Greenwood, Hayti, and Jackson Ward is often quite siloed. But one hundred years ago, people living in black enclaves across the nation were eager to collaborate and learn from one another. The prominent Greenwood leader J.B. Stradford published a travel diary in the Tulsa Star offering lessons about black entrepreneurship he picked up while visiting black neighborhoods such as Harlem. After the Tulsa Race Massacre, John Mitchell Jr. of the Richmond Planet gravely predicted that Greenwood residents would be made scapegoats for the violence and urged white Tulsans to assign blame more fairly. In 1925, Greenwood hosted the annual meeting of the National Negro Business League, attracting black entrepreneurs from across the country and proving the neighborhood’s resilience after the massacre.

Certainly, these business leaders represented only a sliver of the full black experience in these communities. Though “Black Wall Street” is the nickname they often reach for, a more apt moniker would probably be the name the sociologist E. Franklin Frazier gave Durham in 1925: “Capital of the Black Middle Class.” When leaders in these communities espoused American capitalist ideals about the value of hard work and the integrity of a merit-based free market, they earned praise and support from their wealthier white counterparts, as in Durham. When they exposed the hypocrisies present in America’s economic and justice systems, either through editorials, boycotts, or armed resistance, they risked annihilation, as in Tulsa. Former Williams College professor and historian Leslie Brown captured these dynamics quite keenly in her 2008 book Upbuilding Black Durham, which focuses on one black community but offers insight that can be applied to many of them. "As race men, they embraced respectability--industry, thrift, and sobriety--as their own uplift project of rising from slavery's degradations and called upon other men to do the same,” she wrote of the North Carolina Mutual founders. "Against the multifaceted challenges of Jim Crow, black people wore respectability like armor."

*Home ownership figures are for 1910. Still looking for homeownership rates broken down by race in later decades

IThank you for reading. To learn more about the origins of Greenwood, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the community’s astonishing rebirth, check out my narrative nonfiction book Built From the Fire. The book was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and the Washington Post. Buy Built From the Fire on Amazon, Bookshop, or at your local bookseller.

Want to read more stories about neglected black history? Subscribe to Run It Back and receive articles just like this one in your inbox every other week.

Sources

“Great Migration,” Encyclopedia Britannica

“Head of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company Looks Over the Oklahoma Field,” Black Dispatch, Dec. 31, 1920.

Leslie Brown, Upbuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South (University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

Muriel Branch, "Walker, Maggie Lena (1864–1934)" Encyclopedia Virginia.

Museum of Durham History

North Carolina Office of Archives and History, “Durham’s ‘Black Wall Street,’” NCPedia, 2003.

Rodney D. Barfield and John F. Ansley, “North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company,” NCPedia, 2006.

“The Outbreak in Oklahoma,” Richmond Planet, June 4, 1921.

“The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank,” National Park Service.

U.S. Census Bureau, Negro Population 1790-1915 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1918)

Victor Luckerson, “Dismantling Dixie: The Summer the Confederate Monuments Came Crashing Down,” The Ringer, Aug. 17, 2017.

W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Upbuilding of Black Durham: The Success of the Negroes and Their Value to a Tolerant and Helpful Southern City,” World’s Work (January 1912): 334-338

Walter B. Weare, Black Business in the New South (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993)