From There to Here

My journey to becoming a published author winds back to my earliest memories

My book about the history of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, Built From the Fire, releases on May 23. You can pre-order at your local independent bookstore, or at Amazon, Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Books-A-Million.

Grandparents often carry our origin stories, moments that we don’t fully remember but that they polish like fine china through regular retellings. Mommom carried a few about me, mined from our drives in her Oldsmobile around Montgomery, Alabama when I was just four or five years old. She and I had banter–Mommom was a retired first grade teacher, so unlike most adults, she met my mile-a-minute curiosity about the world with genuine interest. I would stand like an overly familiar barfly in the back seat of her car while we talked, until she warned me to sit down and put on my seat belt. During these rides, when she asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I dismissed kindergarten go-to’s like astronaut and fireman. The answer was already clear: “I’m going to be a writer!”

Writing has always been a part of me. My earliest memories involve putting words to the page: pecking at the keys on my family’s old typewriter, writing a short story with my older cousin on our nearly-as-ancient MS-DOS PC, filling the drawer next to my specially designated “writing desk” with a mountain of spiral netbooks. There’s a photo of me clutching one of these journals to my chest in the first grade, its cover emblazoned with the requisite warning of a child just beginning to find themselves: “Keep out!!!”

Clowning with my precious journal in the first grade

At show and tell in elementary school, while my friends did yo-yo tricks and double-jointed bone contortions, I read my short stories. I wrote a parody series of The Magic School Bus that replaced Ms. Frizzle and the gang with me and my classmates. Another story, The Goin’ Buggy Mystery, was a meta-commentary on our second-grade play, in which a rogue student sabotages the production by putting super glue on all the choir risers (I made the culprit a real kid too–sorry, Taylor Elebash). The class loved it, and so did our school principal, Joyce Weldon.

Mrs. Weldon decided that my work was good enough to be published. She had me rewrite the story in my most dignified handwriting and add colored illustrations. Instead of mailing the final manuscript off to Penguin Random House, we took it to the St. James Elementary School teacher’s lounge. No kid had ever stepped foot in that mysterious realm (or so the legend went), but the teacher’s lounge had a binding machine that was used to make spiral notebooks for class handouts. After stepping across the mythical threshold, I watched with my own eyes as Mrs. Weldon fed my carefully rewritten pages and crude drawings into the contraption. Then she handed me something that went beyond the typewriter experiments, MS-DOS printouts and journal scribblings. I was holding my very first book.

—

The impulse to become a journalist came many years after I decided I would be a writer. My older brother told me there was no money in it; I should try to write movies instead. My high school newspaper was defunct by the time I tried to join the staff. But while I was still writing plenty of short stories as a teenager, they were no longer mysteries or adventures. I explored issues like the death penalty, teen suicide, and, quite often, the brutal Jim Crow South that my parents remembered vividly but only ever talked about in passing. I did not want to be transported somewhere else when I wrote; I wanted to unlock more clues about the quietly hostile world that surrounded me. Many of those clues, I soon realized, were hidden in the past.

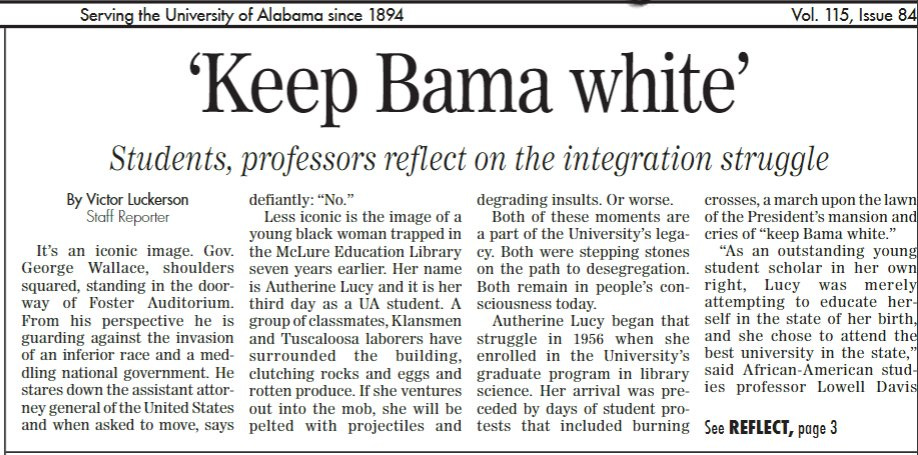

At the University of Alabama, I joined the college newspaper, The Crimson White, before I even attended my first class. My editor assigned me a beat writing historical features, letting me prove my freshman writing chops on soft-focus topics like the legacy of our goofy school mascot, Big Al. As the year progressed, though, I decided to take on heavier history lessons. I pitched a feature on the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door, the infamous attempt by Governor George Wallace to prevent two black students from enrolling at the University in 1963. The Stand is one of the widely known anchor points in Alabama’s civil rights struggle, along with the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Birmingham Campaign, and Bloody Sunday in Selma. I was interested in going deeper on the story, reading sources from the time period to see how the events were received as they were unfolding.

I visited UA’s special collections library to start digging through the archives. There was an ornery microfilm machine in the corner, which seemed even older than the era I was studying, but I eventually tamed it. Poring over old issues of my college newspaper, I found that the all-white editorial staff defended segregation at the University on the basis of “states’ rights”--no huge shock for anyone who grew up in the Deep South. But there were also some big surprises in the CW’s pages. The paper published a letter from William Faulkner championing integration as a matter of “justice and fairness.” But the letter had been written seven years before the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door, about another black UA student I had never heard of: Autherine Lucy.

Lucy was an Alabama native who planned to study library science at UA’s graduate school in 1956, after Brown v. Board wedged the door open for black enrollment. When she arrived on campus, she was greeted by a white mob that included students and members of the Ku Klux Klan (the Klan’s Southern headquarters was in Tuscaloosa, the same town as the University). Lucy was chased around campus, attacked with rotten eggs, and forced to cower in the Education Library where she had expected to quietly learn. The University suspended her, ostensibly for her own safety, and eventually expelled her after she questioned whether campus administrators and police had purposefully allowed the white mob to run rampant.

Digging into Lucy’s story, I felt disoriented. Why hadn’t this been part of my Alabama history classes growing up? Why wasn’t Lucy’s name memorialized on the buildings surrounding the Quad, while Klan members and eugenicists had their legacies etched in stone?

My first article melding journalism and history recounted the little-known story of Autherine Lucy. It was published in my college newspaper during my freshman year.

Rather than focusing on the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door, I decided to center Lucy in my article. I interviewed black classmates and administrators who lamented that the school’s first black student had been “relegated to the footnotes of history.” Lucy’s story was messier than the story of Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood, the black students who successfully defied George Wallace in 1963. There was no inspiring ending about overcoming white hate. But her struggle was no less important. Documenting the moments when white supremacy won out was as critical as celebrating the times when it was beaten back. I began to understand that the path of history was rarely a straight line towards progress. It could be jagged, meandering, and all too often, cyclical.

—

“Don’t you realize that Greenwood was Wakanda before Wakanda?”

It was a sweltering spring evening in May 2018 during my first trip to Tulsa, Oklahoma. Scribbling in my reporter’s notebook, I eyed the small vigil at the corner of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street as local poet Phetote Mshairi conjured the mythology of Black Wall Street.

I was six years into my career as a professional journalist, and visiting Tulsa was very far afield of my day-to-day beat as a technology reporter. Most of my time was spent covering iPhone launch events and tweaks to the Facebook News Feed algorithm. But I’d never lost the curiosity about black history that was sparked by the Autherine Lucy story. Though I mostly wrote about tech, I convinced my editor at The Ringer to send me to Tulsa to write a chronicle of the history of Greenwood. We didn’t have a news hook or a round anniversary number to make people care; I just knew there were too many young people my age who had no idea this place even existed.

The vigil was held on May 31, the 97th anniversary of the race massacre. I had just read historian Hannibal Johnson’s Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District, which painted a vivid picture in my mind of the neighborhood’s former prosperity and its brutal destruction. I knew even before arriving that this place was monumental. I expected to see Tulsa treating it with reverence, the way even Alabama had managed to honor some key locales from the Civil Rights Movement.

But that’s not what I found. As Mshairi recited his poem among the solemn crowd, hundreds more people were streaming past the vigil and toward the art deco sports stadium located just west on Archer Street. The Tulsa Drillers were playing the San Antonio Missions in Double-A baseball.

I once again felt unmoored, watching people glide past a history that was leaping to life within my mind. Tulsa seemed indifferent to what Greenwood meant, in the past or present. And though I had read that the neighborhood triumphantly rebuilt after the race massacre, I saw little evidence of that as I explored its streets for the first time. Much of Greenwood was occupied by construction sites for gleaming new office buildings and a college campus for Oklahoma State, which, along with the baseball stadium, mostly served white residents.

On my first trip to Tulsa in 2018, I participated in a vigil and march commemorating the 97th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Photo courtesy Joseph Rushmore.

When I interviewed Greenwood community members during my visit, the simmering frustration with the neighborhood’s disregard was palpable. “A lot of folks in Tulsa did not want this history to be shared, even today,” Regina Goodwin, a state legislator who represents the Greenwood District, told me then. “They tell us, ‘Oh that happened in the past, you need to forget about it.’ If I were to forget about the past, I would be forgetting myself. I think our families have gone through too much for us to forget about ourselves.”

I went back home to Atlanta and published my piece, one of dozens of magazine-style features I had written as a professional reporter. Usually, I spent three or four days in a community, gathered what I could to craft a compelling story, and then moved on with my life. But something about Greenwood was different. While its physical footprint was unsettlingly empty as I explored it, the vastness of its history felt nearly infinite. And there were so many people still living who could summon that history with ease. With purpose.

I felt compelled to keep writing about this place. And the more I uncovered, the deeper I wanted to dig. Within a couple of months of my first visit, I decided it was time for my life to loop back around to its origin story. I had always said I was going to be a writer, and I had always imagined that meant writing something that could last forever. A book. So I quit my job, packed up my life, and drove West, to Tulsa. It wouldn’t be home, exactly, but it would be a place to find solace in the one ritual that had always brought me peace: capturing our lives through words.

This month, the work of three years living in Tulsa, five years researching Greenwood, almost 30 years of being a writer, bears fruit.

Let the journey begin.

Built From the Fire releases on May 23. Please consider pre-ordering at your local independent bookstore, or at Amazon, Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Books-A-Million.

And if you found this email informative or enlightening, please share it on social media.

I've been with you from the beginning. I'm going to order later todday after I find my Amazon password.