The Critical Next Steps in Tulsa’s Mass Graves Search

Welcome to the first edition of Run It Back, my biweekly newsletter about neglected black history. For the foreseeable future the newsletter will be focused on Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, which I’m currently writing a book about for Random House.

Not far from Greenwood, beneath a large oak tree still brilliantly green in the drab cold of November, I first came upon the graves of Eddie Lockard and Reuben Everett. Their tombstones are modest but resilient, with their shared death date still clearly legible: June 1, 1921. Before that day Reuben was a bricklayer who lived on Archer Street in the heart of Greenwood. Eddie was a member of the Odd Fellows fraternal order and likely a waiter at a restaurant owned by his brother. These men could have lived long and anonymous lives; instead they died as horrific history unfolded. It’s the least we can do to remember them, and the many other victims of the Tulsa race massacre whose names have been lost because they never received a proper burial.

Nearly a century after the massacre, Tulsa is making its most concerted effort ever to find the unknown number of murder victims who were discarded in the hours and days after Greenwood was destroyed by white assailants (the city’s official death count is 26 blacks and 10 whites; estimates go as high as 300). Over the last several months the city has convened a series of public meetings between forensic scientists, historians, politicians, and local activists to develop a plan for locating and potentially excavating the remains of massacre victims. The state medical examiner’s office is involved. A judge may have to issue a warrant for officials to examine private property where bodies are thought to be buried. The search is part archaeological dig, part oral history project and part cold case murder.

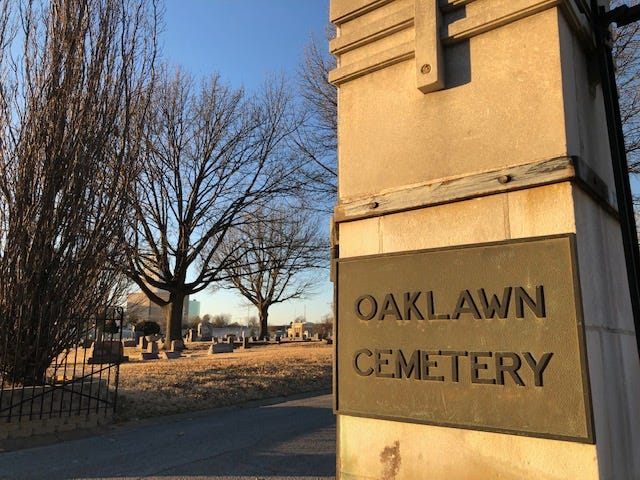

You may have seen the national headlines in December when the city of Tulsa announced that a possible mass grave had been discovered at Oaklawn Cemetery, the same graveyard where Lockard and Everett are buried. Scientists scanned three different sites around the city and determined that a 25 by 30 foot pit at Oaklawn was most consistent with the characteristics of a mass grave. It could hold anywhere between 10 and 100 bodies (or zero if it in fact isn’t a mass grave). The city released a detailed report on its findings to the public at the same time local officials, including Mayor G.T. Bynum, were learning what the researchers had uncovered.

The mayor’s efforts at transparency are a welcome change in a city where information about the massacre was ignored, downplayed or actively suppressed for generations. He promised at the December meeting to “follow this where the truth leads us every step of the way.” But as I’ve talked to some of Tulsa’s black community leaders, who are part of the committee meant to ensure public oversight of the search process, it’s become clear that there are key unaddressed issues that will have to be faced in 2020. I’ll outline a few of those here, so that you can keep the mind as the news develops over the course of the year.

The Complexities of Excavation

The city is developing a feasibility plan this month for how excavation can take place, ironing out legal liability issues and developing a procedure for dealing with unearthed remains. But as the idea of digging up bodies becomes ever more real, political pressure may stiffen against the entire exercise. In the 1990s, Tulsa also convened a committee of experts to look for mass graves, and also deemed Oaklawn the most likely location. But excavation plans were abruptly canceled due to concerns about digging up unrelated grave plots (and, almost certainly, political cold feet). Some of the people who remember the disappointing conclusion of the ‘90s effort don’t expect that to happen again due to the increased number of stakeholders brought into the process. “Twenty years ago we couldn't foster this much public attention,” says Phoebe Stubblefield, a forensic scientist based in Florida who will examine whatever remains are unearthed. “I'm just trying to keep it transparent because the fear of cover-up? Real, historically.”

The Sites Yet to Be Scanned

Booker T. Washington Cemetery, about 15 miles south of Greenwood, has been ID’d as a possible mass grave site but hasn’t yet been investigated.The city claims the owner of the cemetery, which is now known as Rolling Oaks, has refused to let scientists bring their ground-penetrating radar equipment on the land. The owner says the city has dragged its feet developing terms that would protect his property in case it’s damaged. The tension here reflects the ambiguous nature of the search. The mayor has called the process a “homicide investigation” but has been reticent to use the tools associated with such cases, like a court-issued search warrant. He vowed that by the next public meeting in February, the city would have either gotten the owner’s permission to search or begun legal action to get that permission from a judge.

Further north, another cemetery called Crown Hill has its own consistent oral histories about bodies being buried there. The white family that owned the cemetery for two generations claimed it was the site of the mass grave, according to Mike McConnell, who bought the facility in the 2000’s. Massacre survivors have also pointed to Crown Hill as a likely grave site. A large portion of the cemetery that was platted when it opened (in 1909 or earlier, according to tombstones I’ve seen) is today overrun with trees and underbrush because it was never put into formal use--perhaps because black bodies were buried there in secret, McConnell says. At a public meeting in June, McConnell pitched his theory to the search committee members, pointing out the most likely grave location on a massive laminated map. But so far the city has made no mention of Crown Hill as it plans out the rest of its search. “I have discussed this with every mayor since [2002-2006 mayor] Bill LeFortune,” McConnell says. “I don't think they’re truly interested in uncovering the facts, let alone the bodies.”

The Role of Police

The truth of what happened during the massacre could have been pieced together long ago but everyone with first-hand knowledge was buried along with their secrets. The Tulsa Police Department likely played a role in suppressing evidence, according to one of its former officers. Shortly after the ‘90s mass graves investigation, Tulsa historians Scott Ellsworth and Dick Warner heard from a former Tulsa cop named Robert Patty. Patty claimed that in 1973, at the police headquarters, a sergeant named Wayburn Cotton pulled out a cardboard box full of massacre photos--including one of a mass grave filled with black bodies. The photos, if they exist, have never been made public. The mayor has said that an internal search for the photos by the police department turned up no evidence.

Patty reiterated his story in a December interview with the local news station Fox 23. He had never before told the story publicly, promising Cotton he wouldn’t reveal the information while the sergeant lived. Such slow-moving justice frustrates leaders in Tulsa’s black community, forced to grope in the dark for answers that others seem to have sitting below their desks, in their attics, or in the corners of their minds. Robert Turner, the pastor at Greenwood’s Vernon AME Church, is hoping to pressure the police to conduct a more thorough search for the photos and let an independent historian dig through their files. “They die in peace and we live in agony with no justice,” he says. “That only seems to happen to black folks.”

The Reparations Debate

At nearly every mass graves meeting, someone asks whether the end of the search process will result in reparations for descendants of massacre victims. Mayor Bynum has said it’s too early to discuss the issue and that talking about reparations may actually undermine the entire search effort. “One of the issues that they ran into when they did this state commission before was that people started talking about reparations early on,” he said in December. “That spooked a lot of politicians, who then killed the process.”

It’s a shame that the mass graves, by far the most attention-grabbing element of Greenwood’s story, have again become so intertwined with the reparations argument. Search leaders and onlookers alike should avoid conflating an effort to honor the dead with a campaign to find evidence that the massacre was as bad as people claim. We’ll never know the full scope of the horror of 1921 because of a century-long effort to obfuscate the facts. That’s on Tulsa’s leadership across multiple generations. But nothing about this search process can change the facts that we already know--that a black neighborhood was destroyed by white people. The city of Tulsa and the state of Oklahoma failed to protect Greenwood’s residents, to compensate those that survived, or to properly bury those that didn’t. “We don't need any more evidence,” State Rep. Regina Goodwin told me as we left the site of Eddie Lockard’s and Reuben Everett’s graves back in November. “Whether they find any bodies, the case has already been made for reparations.”

If you found this email informative or enlightening, please consider forwarding to a friend. If you are that friend, consider subscribing below. And if you you have comments, critiques, or tips that may help with my research, just reply directly to this email. I’ll be back with more reporting from Tulsa in two weeks.