Run It Back offers carefully researched articles on lesser told parts of black history. But I’m only able to do this work with your help. Please consider getting a paid subscription to Run It Back to help me keep writing these stories and making them available to students, educators and lifelong learners. Subscribe now.

One day last fall, when I was home in Montgomery, I reconnected with a childhood friend who I had not seen in years. Cicely was so excited about my work and had been cheering me on from afar (it’s always a bit surreal when someone you know personally pops up in the YouTube comments for one of your book talks). She is a teacher, mother, and founder of a local children’s museum, so elevating our history is especially important to her. She told me that the next neglected story I needed to dive into was the legacy of Monroe Street.

“What’s Monroe Street?” I asked.

Cicely’s eyes got wide. Monroe Street, she told me, was the street behind Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where black businesses in Montgomery had thrived and the Civil Rights Movement had been incubated. Rosa Parks’ attorney Fred Gray had his law office there, and a drug store on the drag helped coordinate carpools for the Montgomery Bus Boycott. It was our hometown’s equivalent of Greenwood Avenue.

I was embarrassed. The so-called expert on black history didn’t even know the racial geography of his own hometown. But such knowledge gaps are common among many people who grew up in post-Civil Rights, post-urban renewal Montgomery, and other cities across the United States. Often, black people’s history of success has been wiped not only from memory but from the physical landscape. The old Monroe Street buildings were all demolished in the early 1990’s to make way for an office tower, parking lots, and a Holiday Inn.1

My conversation with Cicely reinforced one of the greatest revelations I had while writing my book, one that has largely been missing from common retellings of 20th century black history. There wasn’t one Black Wall Street--there were dozens of them.

--

This month I published a new feature in Smithsonian magazine called “Those Who Stayed.” I wrote historical profiles of three Southern towns that had bustling black business districts just as impressive as Greenwood’s. Richmond was the home of Maggie Walker, the first black woman in the United States to open a bank. Durham’s North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company grew into one of the largest black-owned firms in the country. In Birmingham, A.G. Gaston managed a sprawling empire that included a bank, a funeral home, and a motel.

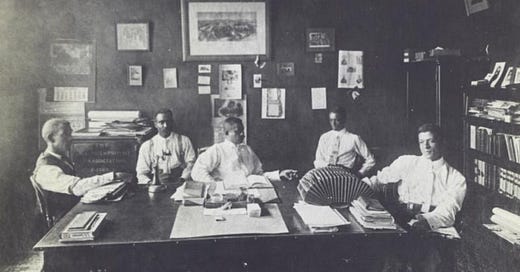

Founders of the North Carolina Mutual Insurance Company in 1911

As a Southerner, I feel it’s important to talk about the success stories that were incubated here, even during the darkest years of Jim Crow. While it’s true that six million black people fled the South during the Great Migration, millions more stayed put. My own family reflects these diverging paths. My mom’s family migrated from Alabama to Chicago starting in the 1940s, but my dad’s family remained in rural Alabama throughout the segregation years. Many Luckersons still reside there. Though everything you’ve read probably says that living in rural Alabama would have been a nightmare in the mid-20th century, when my dad was growing up he and his siblings didn’t have to travel far to reach a “Black Wall Street” of their own. Kinfolks Corner, in the nearby city of Columbus, was a gathering spot every Saturday for black farmers who ventured into town to get their hair cut, buy groceries and connect with old friends.2 I never knew about this place until I started working on my book and asked my dad more about the world that reared him.

Once I realized how widespread these lively black business districts were, it made it easier to see how their success fit patterns we can still emulate today. Most of the districts had financial institutions that re-invested money directly back into their communities--fraternal organizations, banks, insurance companies. Today, black-owned banks are the closest parallel. Organizations like Hope Credit Union, based in Jackson, Mississippi provide loans for homes and new businesses to people who are often excluded from the traditional banking system, just as they were a century ago. Banking with these institutions is a straightforward way to steer capital back towards black communities (I profiled Hope and its response to the pandemic a while back for Wired magazine).

Property ownership is another key to rebuilding black economic independence. Many black business districts were bought out or bulldozed in the 1970’s and ‘80s by commercial developers and urban renewal authorities. That’s one reason that only 3% of black households own commercial real estate today. But there are probably people in your city right now doing what they can to revitalize a hollowed-out black business district. In Greenwood, for example, the Terence Crutcher Foundation recently launched a capital campaign for Greenwood North, a planned community center and marketplace aimed at carrying on the Black Wall Street legacy.

One final thing I noticed about all these neighborhoods--their entrepreneurs didn’t shy away from activism. Women like Maggie Walker organized protests and ran for political office while managing million-dollar enterprises. More conservative businessmen like Birmngham’s A.G. Gaston helped fund civil rights protests even if they didn’t agree on every point of strategy. These battles for equal rights were fought on the local level first, which helped build momentum for national legislation. There are playbooks buried in the past, if we’re willing to thumb through them.

--

Still, there’s more to the history of these places than strategy lessons. Much more.

In April I visited Rochester, New York and got to meet with residents of the historic Clarissa Street. The once-thriving thoroughfare boasted famous local spots like the Pythodd Club, where black residents would go to listen to jazz on Sundays after church. But memories of Clarissa Street’s heyday have dimmed in the years since an interstate highway took out much of the district. In order to preserve the neighborhood’s history, an ongoing project called Clarissa Uprooted pairs local black teenagers with community elders to capture firsthand accounts of the community’s past. This intergenerational research is now on display at the main branch of the Rochester Public Library.

The results are powerful. On my tour of the exhibit, I saw photos of the businesses like the Pythodd Club that had given Clarissa Street life, and I heard oral histories from the people who packed out every storefront. One high school student, Sahiyra Dillard, created a virtual reality experience that layered archival photos and audio into a three-dimensional map of the neighborhood. The exhibit didn’t shy away from the destructive aspects of Clarissa Street’s story, either. I saw a 1966 issue of Rochester’s black newspaper calling urban renewal a “big steal,” as well as parcel acquisition files from displaced property owners. The community wanted to show exactly how legally sanctioned upheaval took place on the ground level.

This kind of knowledge can collapse the space between past and present for young people. When you find out there is more to sift through in your past beyond trauma, It’s an empowering feeling. “Usually when you talk to older people it gets boring,” a young interviewer named Briana Williams said in her conversation with Clarissa Street elder Moses Gilbert. “But I never got bored listening to you guys’ stories…Actually learning something in my own city from my own people is just different. I soaked it up.”

These are just a few of the “Black Wall Streets” I’ve come across in my research and my travels. But there are so many more, hidden in newspaper archives, family photo albums, and warm reminisces at the kitchen table. If we’re not intentional about capturing these stories, they will be forgotten. I’d love to hear more from you about the “Black Wall Street” that was part of your hometown. A neighborhood doesn’t have to be as famous as Greenwood has become for its story to be worth telling.

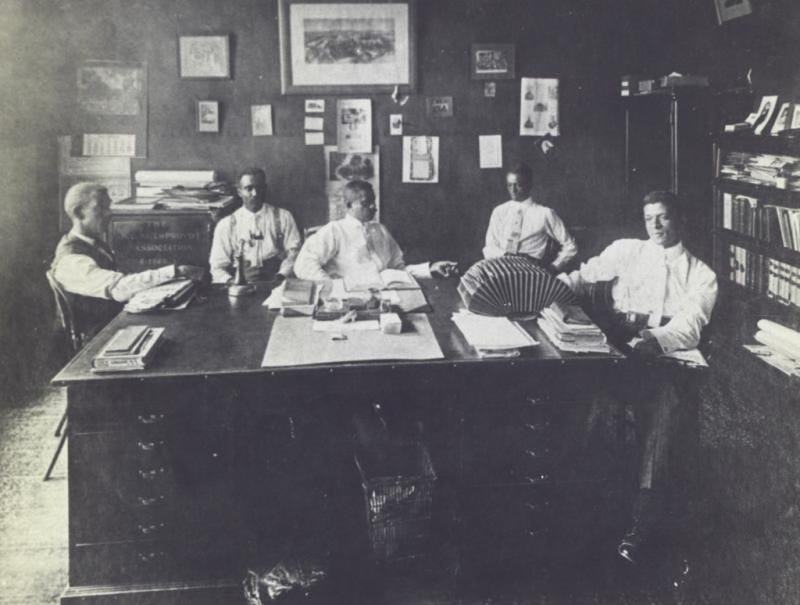

I got to take a tour of the Clarissa Street exhibit in Rochester with two members of the intergenerational research team: Kathy Sprague Dexter and Sahiyra Dillard.

Sources

Lenore Vickey, “Monroe paved with history,” Montgomery Advertiser, Feb. 8, 1998, 1F.

Richard Hyatt, “Kinfolks’ Corner,” Columbus Ledger Chattahoochee Magazine, Aug. 27, 1981, 1.

Great Smithsonian article, Victor! I read that prior to seeing you mention it in today’s piece. Keep up the good work.

I was going to mention Maggie Walker and Jackson Ward - Richmond's my hometown - but you're already there. :)