The Story of Black Wall Street: The Women of Greenwood

Female entrepreneurs not only contributed to the prosperity of early Greenwood but preserved the history of it

Download a PDF version of this article for the classroom

It was instantly the crown jewel of Greenwood: a $10,000 theater housed in a two-story brick building in the heart of the business district. Sometimes it was an entertainment hub--residents could visit to watch vaudeville acts, boxing bouts, and the biggest silent films of the day. Other times it was a community center, hosting the graduation ceremony for the neighborhood high school. Occasionally, it was a strategic headquarters where Greenwood leaders would coordinate plans to battle the legal encroachments of Jim Crow. No other location in Greenwood served so many needs in so many contexts. The venue’s name, glowing on the electric marquee as people streamed in after dark, fit all too well: the Dreamland Theater.

According to the newspapers of the time, John Williams deserved all the credit for early Greenwood’s most famous business. The Tulsa Star praised him as a bold risk-taker. The Tulsa World, the city’s leading white daily, called him the “Negro Rockefeller.” But when Williams purchased the lot that would become the Dreamland in May 1914, it was he and his wife Loula whose names both appeared on the land deed. And by the time the Dreamland had become a community fixture towards the end of the decade, Loula owned it outright. In 1919, she signed an affidavit declaring that she was the sole owner of the theater, while John independently owned the East End Garage.

Loula was older than John, and uninterested in living in his shadow. She used money she earned working as a schoolteacher to open a corner store in Tulsa in 1909, the same year she and John were married. That store would eventually grow into the Williams Confectionery, a sugary delight on Greenwood Avenue with a soda fountain, popcorn machines, and mountainous jars of candy. She bought the property under her maiden name, and owned it herself along with the Dreamland. When the Tulsa Star released a booster edition in 1914 profiling Oklahoma’s leading black entrepreneurs, Loula and John each received separate profiles. The newspaper called her “unquestionably the foremost business woman of the state, among Negro women.”

The story of Greenwood’s history is often anchored by men: J.B. Stradford, O.W. Gurley, A.J. Smitherman. Women tend to play a supporting role in the narrative--because many worked as domestics in white households, the days were off and able to shop and relax were the liveliest days in the neighborhood.

But who were they? History has been designed to omit large portions of the black experience, and the issue is compounded for black women. Something as simple as a maiden name, a key to unlocking a woman’s life before marriage in census records, is often tough to track down. In The Tulsa Star and other newspapers of the period, women are often referred to simply by their husband’s names (as in “Mrs. John Williams”). Media coverage of the era is fixated on local politics, which means it is fixated on men, who were the only people who could vote in Oklahoma until 1918. By the time events in Greenwood wound their way to Tulsa’s white community, a woman’s accomplishments would be even further diminished--when the Tulsa World praised John Williams, the paper ID’d him as the owner of the confectionery, even though it was Loula’s business.

Tulsa’s city directory offered a few more clues about the entrepreneurial women of Greenwood. Lula Lacy owned a restaurant on Archer Street. Dora Wells ran a dressmaking shop a block away. Greenwood was also home to female grocers (Mary Ware), tailors (Abbie Funches), and landlords (Marie Johnson). Mabel Little worked a pittance-paying job at at a white hotel when she arrived in Tulsa in 1913; she ran a popular beauty shop on Greenwood Avenue just four years later. Little would go on to become a revered community leader, witnessing every triumph and tragedy in her neighborhood until she passed away in 2001, at 104 years old.

While there are some memoirs, newspaper columns, and courtroom testimonies from men who lived in Greenwood, the record of women describing their lives in their own words is disappointingly scant. One document stands out. Mary Jones Parrish, a stenographer from Rochester, New York who ran a school teaching typing, was drawn to Tulsa because of how effectively its black community worked together to build up collective prosperity. Like thousands of other Greenwood residents, she was forced from her home on May 31, 1921 as whites bore down on the community.

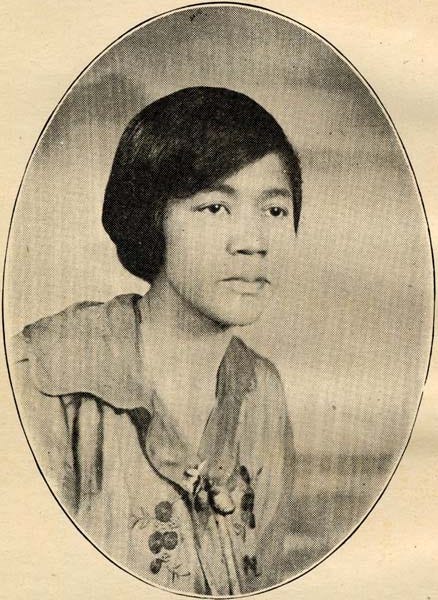

Mary Jones Parrish, as featured in her book about the race massacre

Parrish wrote down everything that happened from the moment her daughter looked out of their home’s window and told her, “Mother I see men with guns.” She described fleeing north of the city, hiding out in the homes of good Samaritans for two days, riding back into town on a Red Cross truck as whites looked on with bemusement, and accepting second-hand clothes for her daughter at the equivalent of a refugee camp after her home had been destroyed.

Then, critically, she gathered recollections from about two dozen other Greenwood residents, who recounted their own vivid memories of the massacre and its immediate aftermath. This is, by far, the most comprehensive collection of black eye witnesses speaking about the event. Without Parrish’s journalistic efforts, the truth of what happened in Greenwood may never have been fully known. Events of the Tulsa Disaster is the most essential primary text about what happened in 1921. But Parrish’s life after the attack has faded into the haze of forgotten history. Like many other women in Greenwood, she’s become a footnote in a story she herself helped establish.

History has been designed to omit large portions of the black experience, and the issue is compounded for black women. The opportunity to collect the voices of the women of early Greenwood is now lost forever, but modern tools make it much easier to scrape the fragments of the past and at least attempt to paint a fuller picture.

Thank you for reading. To learn more about the origins of Greenwood, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the community’s astonishing rebirth, check out my narrative nonfiction book Built From the Fire. The book was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and the Washington Post, and it has been named a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. Buy Built From the Fire on Amazon, Bookshop, or at your local bookseller.

Want to read more stories about neglected black history? Subscribe to Run It Back and receive articles just like this one in your inbox every other week.

Sources

Database of Greenwood businesses provided by Oklahoma Historical Society

“J.W. Williams, Automobile Expert.” Tulsa Star. 19 Aug 1914.

“Mrs. Lulu ‘Cotton’ Williams, Williams Confectionery.” Tulsa Star. 19 Aug 1914.

“New Theatre Draws the Crowd.” Tulsa Star. 5 Sept 1914.

“Negro Rockefeller.” The Morning Tulsa Daily World. 4 Jul 1915.

Parrish, Mary Jones. Events of the Tulsa Disaster. 1923.

Tulsa County Courthouse records