The Story of Black Wall Street: Why Greenwood Flourished

A prosperous black middle class emerged in Tulsa for reasons that were both specific to Oklahoma and common throughout the U.S.

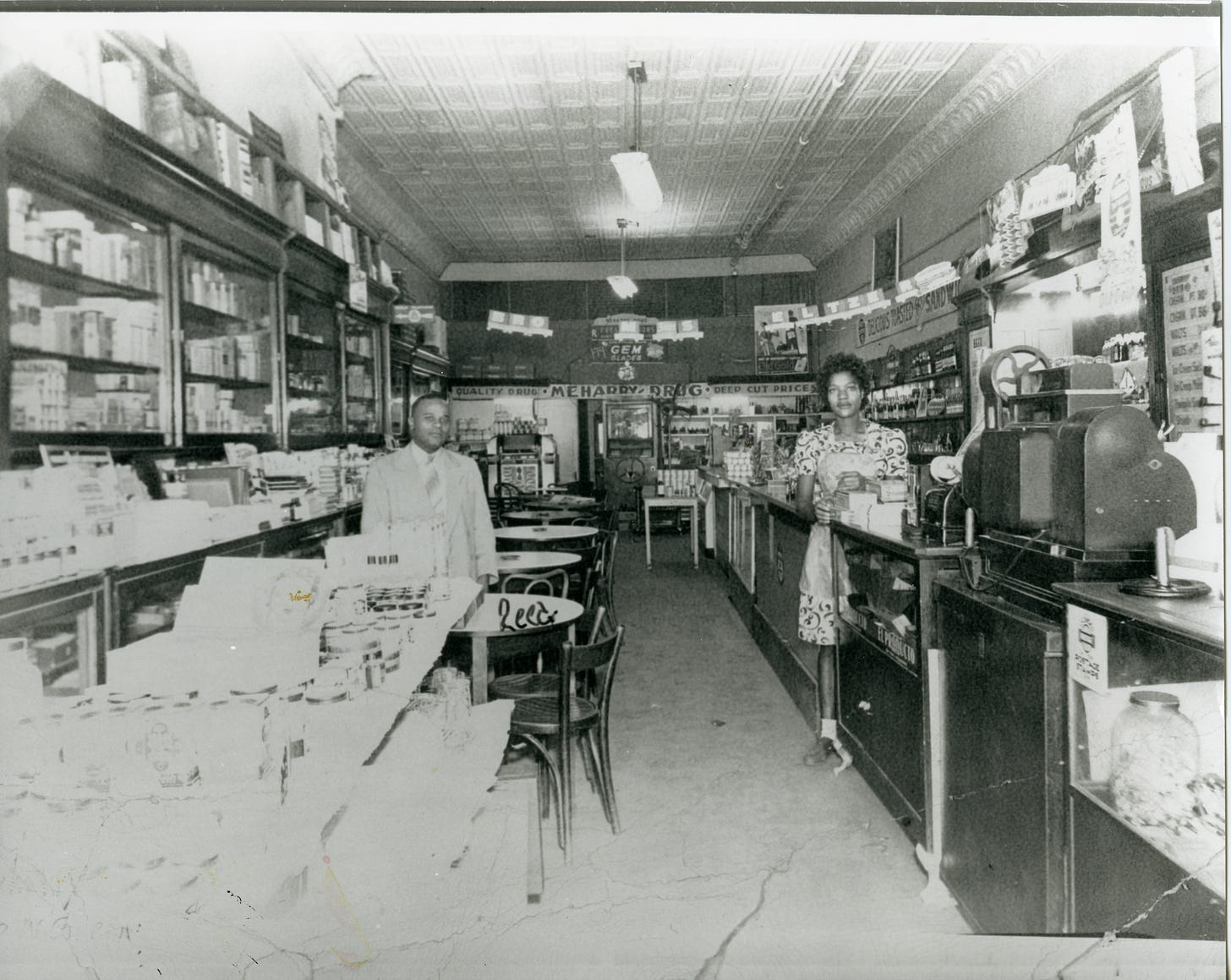

Meharry Drug Store in the Greenwood District in the 1930s. Photo courtesy Greenwood Cultural Center.

Download PDF version of this article for the classroom

When Mary Jones Parrish stepped outside the Frisco Train Depot near downtown Tulsa and cast her eyes northward, she knew she’d stumbled upon a special place. It was 1918, and the humble little neighborhood of Greenwood, begun with a single grocery store in 1905, was thriving. The Dreamland Theater’s glittering marquee drew in visitors every night. The Palm Garden Athletic Club offered heavyweight boxing bouts between some of the nation’s best black fighters. There were restaurants, pool halls, tailors, beauticians, doctors, lawyers, and more, all operating within a few blocks of the railroad tracks. What captivated Parrish most, though, were the warm smiles of the people sauntering into and out of all these establishments. Despite being hemmed in by the institutional racism Oklahoma was erecting statute by statute, Greenwood seemed at peace with itself.

"I came not to Tulsa as many came, lured by the dream of making money and bettering myself in the financial world,” Parrish said, “but because of the wonderful co-operation I observed among our people, and especially the harmony of spirit and action that existed between the business men and women."

Why Greenwood? That’s one of the many questions I’m trying to answer with my book. It’s more than a little counterintuitive that a small black population in a small southwestern city would build a community that Parrish dubbed “The Negro’s Wall Street.” Segregation created a community need for black-owned businesses not only in Oklahoma but around the country. Meanwhile, the widespread championing of black capitalism by leaders such as Booker T. Washington and, early in his life, W.E.B. Du Bois, aligned black entrepreneurship with the perennial battle for civil and human rights. This was a national phenomenon, not just a Greenwood one. Other versions of the “Negro’s Wall Street” emerged in places like Richmond, Virginia; Durham, North Carolina; and Birmingham, Alabama.

It’s also important to understand that the mythic status Greenwood has attained as a kind of lost black utopia (the introduction of my very first story about the neighborhood includes a quote about Wakanda) doesn’t capture the full lived experience there. Outside the successful business district, living conditions for many Greenwood residents were poor. Electricity and running water were rare. An effort to convince the city to pave Greenwood Avenue stretched on for months. While members of the entrepreneurial class that persist in Black Wall Street mythology resided in large, elegant homes, many community members lived in shanties. “Over here in North Tulsa, we didn't have electric lights, no gas, no water, no paved streets, and only one family in the whole North Tulsa area had a telephone,” Robert Fairchild, a massacre survivor, recalled decades later.

As I’ve done more research, I’ve drifted away from the impulse to try to prove that Greenwood was the richest or best or most prosperous black community in America. As Parrish’s words indicate, the community mattered because of the ways in which it emphasized collective action and partnership rather than the triumphs of the individual. The fact that people only a generation removed from slavery--some of them even born into enslavement--carved out the success they did in an intensely racially hostile environment is worthy of praise, remembrance, and study. Here are a few of the reasons specific to Greenwood that this particular version of Black Wall Street flourished. They all offer lessons about how black people might thrive economically today.

Freedmen and the Importance of Land Ownership

As I’ve explained before, black people were a powerful class of landowners in Oklahoma. When the federal government forced Native Americans to abandon communal land ownership in favor of individual allotments, more than two million acres of land were granted to the black freedmen who were members of the Five Tribes. Much of this land was quickly sold into the hands of conniving white land developers, but a sizable portion remained under black ownership. In 1920, black farmers still controlled almost half a million acres of land in Oklahoma, and a much larger percentage of black farmers there owned their land compared to in the surrounding states. In Wagoner County, which is just east of Tulsa, nearly half of the farmers who owned their own land were non-white. Some of these black farmers lived in Greenwood or conducted business there. W.H. Smith, a fruit dealer in the neighborhood, bought a farm in Wagoner in the fall of 1918. He viewed the purchase as a bet on the future prosperity of Tulsa, and Greenwood in particular.

Some freedman lands yielded oil rather than crops, leading to vast fortunes for their owners. Because some of these freedmen lived in Tulsa, a portion of that wealth circulated within the Greenwood economy. Robert H.P. Watson, a Creek freedman who lived a block over from Greenwood Avenue, had at least four oil-producing wells drilled into his land allotment in the early 1910’s. When he came of age in 1919, his legal guardian granted him a lump sum payment of $6,794 (roughly $100,000 adjusting for inflation). His mother Aurelia Watson also received monthly payments from his oil windfall, and she eventually owned and operated a $5,000 rooming house in Greenwood. It was the money black people earned from land ownership that ultimately found its way into the cash registers of Greenwood’s mom-and-pop businesses.

The All-Black Town Ecosystem

In the early 1900’s Greenwood was surrounded by all-black towns, municipalities that were completely governed and largely populated by black residents. There were seven of these towns in the counties surrounding Tulsa, and at least 50 emerged throughout Oklahoma between 1865 and 1920. These towns, by the very nature of their existence, had to produce a black professional class--lawyers and doctors and teachers and mayors to keep their societies functioning. As Greenwood’s fortunes rose and the appeal of the black town declined, many of the towns’ residents made a home in Tulsa. B.C. Franklin, a prominent Greenwood lawyer who played a key role in preserving the community after the massacre, came to Tulsa in 1921 from Rentiesville, an all-black town in eastern Oklahoma. Even for those who continued to reside in the smaller towns, Greenwood would have been an urban magnet they might visit to shop, socialize, or conduct business. The streak of black independence in Oklahoma allowed different communities to feed off each others’ success.

A Spirit of Collaboration

Many of Greenwood’s most famous landmarks were only built because black folks were willing to work together for a greater cause. In 1913, J.B. Stradford offered A.J. Smitherman a blank-check loan to help him launch the Tulsa Star (Smitherman ultimately didn’t need the money, but the gesture created a permanent bond between the two men). Mt. Zion Baptist Church, the most opulent structure in the neighborhood before the massacre, was built thanks to a fundraising drive that brought church coffers from $750.15 to $42,000 in the span of five years. A library that Stradford operated, which was not initially part of the city’s government-funded library system, built an impressive collection from books donated by the community. "It is the duty of the citizenship of our race in Tulsa to unite in some common cause…and adhere to that thing until we have made it a glaring success,” Stradford said in a 1914 speech.

Of course, Greenwood’s greatest test of solidarity would come after the massacre, when white Tulsans largely ignored the neighborhood’s plight and black Tulsans had to chart a new future for themselves. But in a moment of crisis, people have to apply the lessons they learn in their day-to-day lives. The collaborative environment in early Greenwood proved an effective teacher.

Thank you for reading. To learn more about the origins of Greenwood, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the community’s astonishing rebirth, check out my narrative nonfiction book Built From the Fire. The book was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and the Washington Post. Buy Built From the Fire on Amazon, Bookshop, or at your local bookseller.

Want to read more stories about neglected black history? Subscribe to Run It Back and receive articles just like this one in your inbox every other week.

Sources

1920 U.S. Census.

1930 U.S. Census.

“Annual Address of President Stradford.” Tulsa Star. Feb. 14 1914.

“Coming Bout to Be a Hummer.” Tulsa Star. Nov. 13 1915.

Fairchild, Robert. Interviewed by Ruth Sigler Avery in 1976. Ruth Sigler Avery Collection. Oklahoma State University-Tulsa.

Franklin, B.C. My Life and an Era: The Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin. 1997.

“The Fruit Man Purchased the McGregory Property.” Tulsa Star. Oct. 19 1918.

Hirsch, James. Riot and Remembrance. 2002.

“New City Library Board Is Appointed.” Tulsa Democrat. Nov. 14 1916.

O’Dell, Larry. “All-Black Towns.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

Parrish, Mary Jones. Events of the Tulsa Disaster. 1923

“Public Library Organized.” Tulsa Star. Feb. 21 1914.

Robert H.P. Watson Guardianship Records. Tulsa County Courthouse.

Smitherman, A.J. “Launching the Tulsa Star.” Empire Star. March 25 1961.

Williams, Levada. “Monthly Report of Colored Public Library.” Tulsa Star. Aug. 8 1913.

Work, Monroe. Negro Year Book: An Annual Encylopedia of the Negro, 1921-1922. 1922.