The Story of Black Wall Street: How They Rebuilt

Through a mixture of hubris and active malice, Tulsa city leaders undermined the rebuilding of Greenwood. Black people brought the neighborhood back anyway.

Photograph of tent home after the Tulsa Race Riot, June 1, 1921. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Download PDF version of this article for the classroom

The tents stretched across the burned-out prairieland for acres, surrounded by dirt and rubble and trees stripped bare of all their foliage. Where the Dreamland Theater had once welcomed jubilant patrons every night, there was a tent. On Independence Street, behind an unnamed man standing sentry over his personal wreckage, there was a tent. The Red Cross officially furnished more than 400 of them to Greenwood residents, but more than 1,200 homes in the neighborhood were destroyed, which means that most families actually found their own way in the brutal aftermath of the massacre. Some crowded into the houses of family members whose homes had survived. Others erected their own makeshift shelters amidst the destruction. Many must have assumed that no one was ever going to step in and help them, so they might as well help themselves.

Immediately after the massacre, city leaders signaled that they intended to rush to Greenwood’s aid. "The city and county is legally liable for every dollar of the damage which has been done,” Loyal J. Martin, a former Tulsa mayor, said at a meeting of white businessmen the day after the massacre. “Other cities have had to pay the bill of race riots, and we shall have to do so probably because we have neglected our duty as citizens."

Martin became the chair of the Public Welfare Committee, the city’s agency for coordinating reconstruction efforts. Because the race massacre had been a national news story, landing on the front page of the New York Times, offers poured in from around the United States offering to aid Tulsa’s newly destitute citizens. Martin fielded the telegraphs himself. But he believed Tulsa should go it alone in rebuilding Greenwood, and his personal opinion became institutional policy. “I telegraphed back that this was our trouble,” he later said. “We were to blame for it and...we would take care of it.”

The Public Welfare Committee developed a three-pronged strategy for aiding Greenwood: soliciting donations from white Tulsans, deploying city and county funds, and enlisting the help of the Red Cross (the state of Oklahoma opted out of helping on June 3, with the governor writing in a telegram, “There are no state funds available for the aid of Tulsa Race Riot”). The plan may have been motivated by a sense of moral duty, but it was also an effort to protect Tulsa’s image and prevent the Oil Capital of the World from being branded a dangerous, lawless backwater.

Calls for donations had a limited impact. In a city where white church congregations could raise $50,000 for new buildings within days, private donations in the monthslong relief campaign ultimately totaled roughly $25,000 ($374,000 in today’s dollars). A Public Welfare Committee member called the figures “distressingly small” as the campaign inched along, and city officials began to second-guess Loyal Martin’s decision to turn down outside aid.

Convincing the city to allocate funds toward relief also proved a challenge. The city commission briefly toyed with the idea of using government emergency funds to “fortify” city hall rather than aid black residents. Weeks after the massacre, Tulsa Mayor T.D. Evans ousted the original Public Welfare Committee, which had at least publicly declared an intention to rebuild Greenwood, and installed a “Reconstruction Committee” comprised of real estate developers who wanted the land for themselves. This new committee used stalling tactics to slow Greenwood’s redevelopment, demanding weekslong audits of how relief funds were being spent before allocating more money. Tate Brady, the Ku Klux Klan member and close ally of the man spearheading the real estate scheme to move blacks farther north, was the new committee’s vice chairman.

The only white-led institution that understood the race massacre as an actual humanitarian crisis was the Red Cross. Arriving in Tulsa the day after the city burned, Red Cross relief operations director Maurice Willows ultimately spent the rest of the year in Greenwood, aiding black residents and sparring with city leaders. When massacre victims’ meager tents flooded that summer, which was often, the Red Cross provided shelter in the neighborhood high school, and later in a standalone headquarters. At city hall, Willows needled Evans and the commissioners into providing a small amount of financial assistance--between about $10,000 and $20,000--to help keep Greenwood residents fed and housed as winter approached. Mary Jones Parrish, a Greenwood teacher and writer, praised the Red Cross workers as “angels of mercy,” and a hospital built in the neighborhood after the massacre was named after Willows. But even as the Red Cross offered vital financial and logistical help, it was the black people of Tulsa who wielded the hammers, saws and sewing machines that built Greenwood anew.

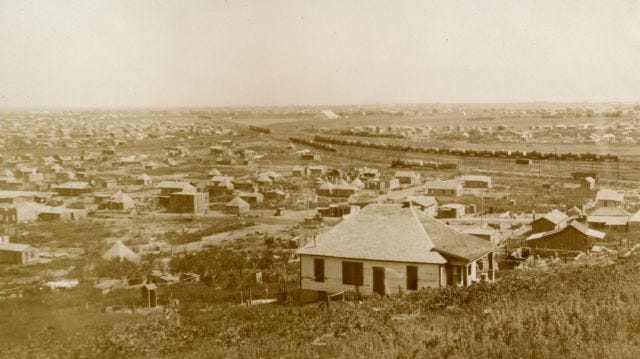

Temporary housing constructed in the Greenwood District by the American Red Cross following the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. The image is taken from a hill looking down at the newly constructed houses. Photo courtesy Tulsa Historical Society

“The struggle to regain a normal existence was hard,” Mabel Little recalled decades later. She and her husband Pressley had owned a beauty salon, a café, a home and car; all of it was destroyed or stolen during the massacre. With the core business district a barren wasteland, they ventured farther north and built a modest three-room house at the corner of Marshall Street and Greenwood Avenue. “We had to cut corn stalks and clear the ground in order to build the house,” she said. “There was no electricity, water, or gas. We had to cook outdoors with wood as fuel. We had to dig wells for drinking water.”

The labor of rebuilding Greenwood fell to the people who had been ejected from their own homes. With the exception of “sick or helpless people,” the Red Cross expected blacks to take a stack of donated lumber, round up a group of family members and friends, and get to rebuilding. At the Red Cross headquarters, sewing machines whirred as black women and girls were tasked with making clothes and bedding to replace all that had been burned by the white mob. Some, but not all of this work was compensated with small wages provided by the Red Cross. But the by-your-own-bootstraps mentality that is so deeply ingrained in American culture framed the entire rebuilding effort, as even well-meaning whites tried to cast a racist massacre as a teachable moment.

Given the circumstances, though, Greenwood arose again remarkably quickly. The tents that flooded during downpours were upgraded with wooden flooring and eventually replaced by 225 wooden one-room and two-room houses. Entrepreneurs started to replace the bricks of the structures that anchored the business district as early as August. While white Tulsa turned away outside aid, the Colored Citizens’ Relief Committee, led by Greenwood pioneer O.W. Gurley, solicited funds from black communities around the nation. Key black civic organizations like the NAACP and the National Medical Association raised money on Greenwood’s behalf, and black fraternal organizations like the American Woodsmen stepped in to offer loans when Tulsa banks wouldn’t. By Christmas, Greenwood had rebuilt 664 frame shacks, 48 brick or cement buildings, and 4 frame churches.

Greenwood was on its way back to prosperity, thanks to the path toward recovery that residents had charted for themselves. "Seven months have elapsed since the trouble started, and on this date, December 31st, no rehabilitation nor practical reconstruction program has been outlined by the city government,” Maurice Willows wrote in one of his final reports from Tulsa. “The so-called Reconstruction Committee has gone out of existence without recording any constructive results."

Thank you for reading. To learn more about the origins of Greenwood, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the community’s astonishing rebirth, check out my narrative nonfiction book Built From the Fire. The book was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and the Washington Post. Buy Built From the Fire on Amazon, Bookshop, or at your local bookseller.

Want to read more stories about neglected black history? Subscribe to Run It Back and receive articles just like this one in your inbox every other week.

Sources

“Arsenal Fund is Demanded by Red Cross.” Tulsa World. June 30 1921.

Autobiography by Loyal J. Martin. Ruth Sigler Avery Collection (Series 1, Box 5). Oklahoma State University-Tulsa, Tulsa.

Carlos Moreno, “The Victory of Greenwood: Mabel B. Little,” New Tulsa Star.

Mabel Little, interview conducted by Ruth Sigler Avery, Ruth Sigler Avery Collection (Series 1, Box 4). Oklahoma State University-Tulsa, Tulsa.

“Martin Blames Riot to Lax City Hall Rule.” Tulsa Tribune. June 2 1921.

Mary Jones Parrish. Events of the Tulsa Disaster.

Maurice Willows’ Red Cross Report. Jan. 22, 1921. Ruth Sigler Avery Collection (Series 1, Box 1). Oklahoma State University-Tulsa, Tulsa.

“Red Cross Is on the Verge of Break With City Hall.” Tulsa Tribune. Aug. 10 1921.

After reading these articles they are a reminder that now more than ever wee will always have to care for our own.