A People's History

I hired my 13-year-old cousin to be a research assistant on my book. He's now a high school senior. We talked about all that he learned about race in America.

My book about the history of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, Built From the Fire, is almost here! You can pre-order at your local independent bookstore, or at Amazon, Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Books-A-Million.

In this country, letting a black child learn their own history has always been deemed a radical act. “Knowledge of books…serves to sharpen [the Negro’s] cunning, breeds hopes that cannot be fulfilled, inspires aspirations that cannot be gratified,” declared Mississippi Governor James Vardaman in 1904. Earlier this year, Florida’s education commissioner argued that teaching students the writings of black scholars like bell hooks and Angela Davis was “indoctrination masquerading as education.” Knowledge is dangerous, a growing chorus of parents, pundits, and legislators tell us. They insist that the wrong kind might tear apart the very fabric of our society.

A few years ago, before “critical race theory” entered the popular lexicon and the list of banned books began growing longer with each school board meeting, I entered into a radical pact with my younger cousin, Stanley Stoutamire, Jr. When he was just 13, I asked Stanley if he wanted to help me conduct research for a book I was writing about the history of Greenwood and the Tulsa Race Massacre.

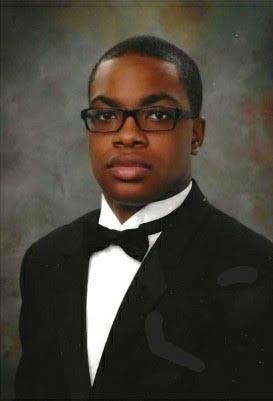

Stanley and I about a year before I hired him to be a research assistant for my book.

It didn’t seem so transgressive at the time. Stanley had always been one of the smartest people in my orbit. When he was five years old, he dreamed of being a weatherman, so when he came to my college graduation, he picked out a meteorology study guide from the campus bookstore (written for twentysomethings, not kindergarteners). Later, Stanley became interested in journalism, writing, and history. He volunteered at his neighborhood library and asked me to come speak to his seventh grade creative writing class. Though he was young, I was confident that hiring Stanley would be a boon for both of us.

In January 2020, I emailed Stanley my 90-page book proposal and gave him a few weeks to look it over. He was 14 by then and had just finished his first semester of high school in Birmingham, Alabama. As he pored over the document, which included a detailed account of Greenwood’s destruction and photos of the neighborhood set ablaze, Stanley was shocked by what he was reading. He had never been taught about the Tulsa Race Massacre in class. “I had almost, like, a sense of betrayal,” he told me recently. “The Tulsa Race Massacre, when you actually look at it, is such a significant event in American history. And it just doesn't actually exist in what we think of as American history.”

Stanley had a lot of questions. How was a machine gun used on people in Greenwood, and what happened to the weapon afterwards? Why had the city of Tulsa never completed its search for mass graves of massacre victims? Were there similar massacres in other cities–other bits of our country’s history he had never learned about?

I let Stanley choose where to focus his research, and he decided to initially explore World War I and the Red Summer, a period of social upheaval and racial violence that directly preceded the massacre. He was the youngest of about ten researchers and fact-checkers who worked on Built From the Fire, but I treated him like he was a college undergrad. Stanley read a book about black soldiers’ mistreatment during World War I and another about the race riots and massacres that wracked the country in 1919. He highlighted key passages from these books, which helped me shape my own characterization of that period.

Stanley officially started working for me on May 26, 2020, the day after George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer. As he read about the nationwide violence of 1919, when black people in dozens of cities challenged racist conventions and were met with a ferocious white backlash, he saw similar images being beamed to the world each day as the protests following Floyd’s killing spread to thousands of cities and towns around the world. Stanley was only beginning to learn about the untold history of America, but the parallels were clear. A 1919 quote from Richard Wright in one of his assigned books jumped out at him: “Do not be afraid or lose heart because of these riots,” Wright told black people then. “They are merely symptoms of the protest of your entrance into a higher sphere of American citizenship.”

Stanley saw things similarly. “We are seeing true progress because of the horrors of this summer,” he wrote in a note to me not long after Floyd’s murder. “Because there was nothing else to do but watch a lynching, the nation was galvanized into action.” So much social upheaval in the nation’s history, he was beginning to realize, was sparked by brutality against black people.

Stanley continued to work with me when he entered the 10th grade, then on into the 11th. He read more books about the history of black Nashville, black soldiers’ treatment during World War II, and the Atlanta funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr. He reviewed lawsuits filed by Tulsa Race Massacre survivors against insurance companies and analyzed land records to help me with a chapter on redlining. He read several years’ worth of issues of the Oklahoma Eagle, focusing on the newspaper’s fight for black jobs at a Tulsa aircraft manufacturing plant. “There's so much that I didn't know about black history that I learned because of this,” Stanley told me. “I had never even heard of Stokely Carmichael. I had never even heard about the Fisk Jubilee Singers that traveled around the globe. I had no idea what it was like being black in America all the way back in the early 1900s. And I didn't realize how similar it would be to being black in America now.”

Stanley is now a high school senior and among the top students in his class.

The current backlash placing race at the center of some conversations in the classroom is undergirded by a fear that young people will be psychologically damaged if they are exposed to dark parts of our nation’s past—if they are forced to reckon with how their own experiences and privileges are shaped by those events. While much of the national attention has been focused on Florida and Ron DeSantis’s duel with The College Board, Oklahoma was one of the first states to pass a law limiting what can be taught in the classroom in early 2021. The law declares that students should not be made to feel “discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex.”

It has mostly been white parents leading the charge against works that delve too deeply into issues of race, gender, or sexuality, but it is the students from marginalized groups who absorb the lessons from these texts most viscerally. For black students like my cousin Stanley, the full excavation of America’s past reveals a harsher existence for their ancestors than many had previously realized. But learning more about what black people had been through, beyond slavery and the Civil Rights Movement, actually made Stanley want to discover more. Rather than feeling “anguish,” he felt inspired when he saw his predecessors taking steps to better their lot time and again, even after utter devastation.

“Black history has to have some sort of message that can't just be: slavery ended, then Rosa Parks got kicked off the bus, then Martin Luther King had a dream, and then everyone was happy,” Stanley told me. “There’s a missing piece of the story of America. And it's not actually missing. It's been locked up in a cabinet so that way, the picture looks nicer. This puzzle that is America can't be complete, until that missing piece of black history is added.”

Thank you, Stanley, for all your work on this project.

I so appreciate both what you have done for your nephew and what you are doing to educate us all. I grew up in Oklahoma in the 70's and was appalled this wasn't taught in schools. I was deep into discovering Harvey Milk and the LGBTQ movement during my high school years while my friends were being harassed for their sensuality. I look forward to reading your book!

This is SO exciting! I've pre-ordered my copy and can't wait to read your book. Congratulations and kudos on your responsible mentorship.