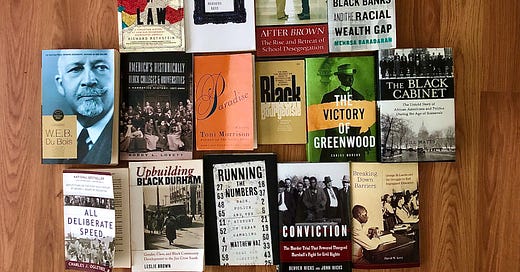

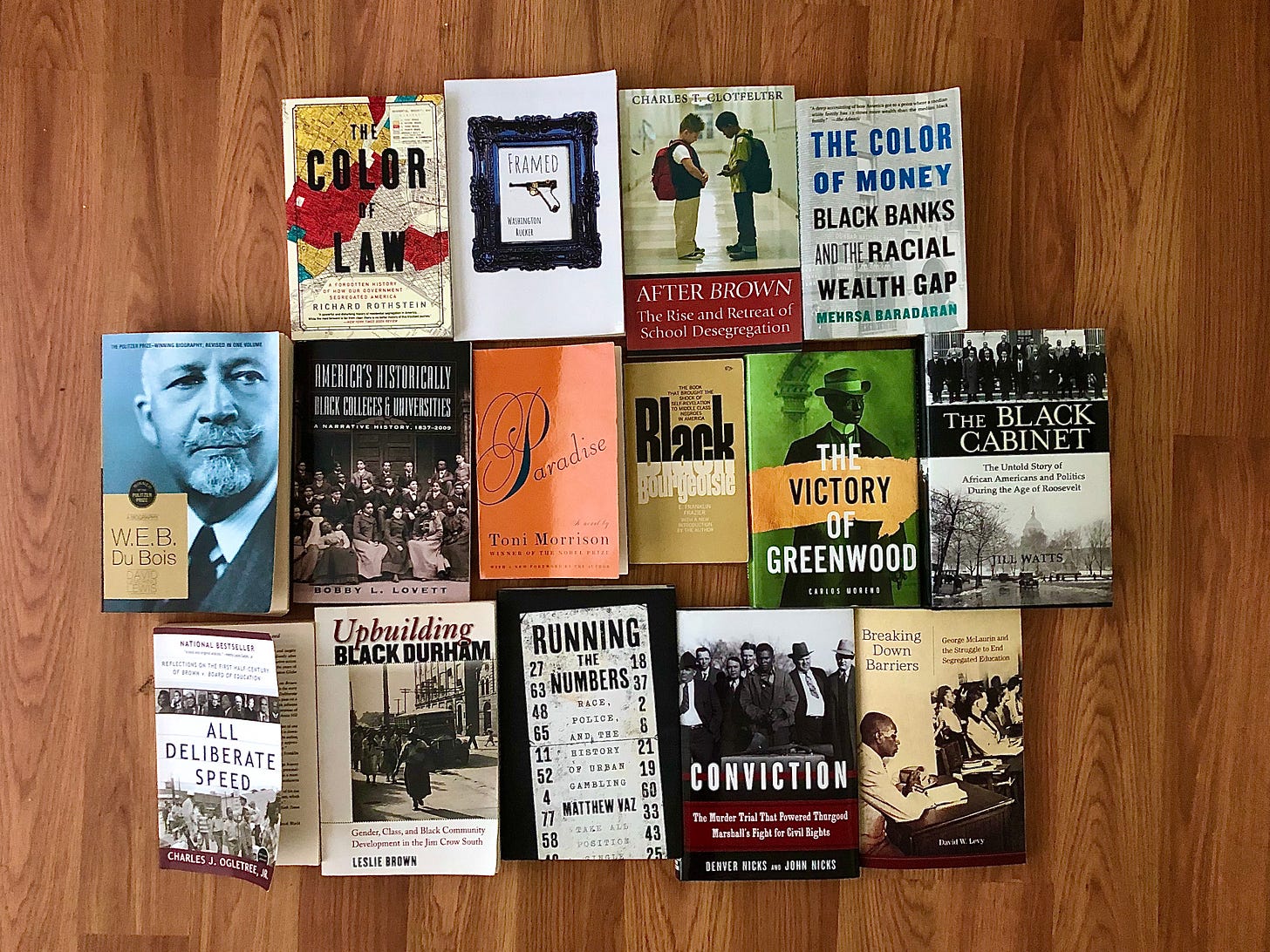

Some books I’ve been reading for the last few months as part of my research

Yesterday, the manuscript of Built From the Fire reached 97,000 words. It was one of the more frustrating days of the writing process so far. The organizational part of my mind has already laid out the scenes of a chapter I’m working on about desegregation in Oklahoma, but the creative half of my mind was in open rebellion. I’ve been running with the “check engine” light on since around the time I stopped writing this newsletter in June, when the emotional and logistical exhaustion of the 100-year anniversary of the massacre gave way to a new round of ever-more-pressing deadlines for my book and various freelance assignments. I’m tired; you’re tired. So it goes in the pandemic era.

But there was something else wrong yesterday. I felt a spiking anxiety--always gnawing at me but occasionally taking vicious, ragged bites--that I’m simply not up to the task of writing this book. I’m currently reading Toni Morrison’s 1997 novel Paradise in a book club my girlfriend and I started (the two of us are the whole club). Paradise is about an all-black town in Oklahoma that is a photographic negative of Black Wall Street mythology; the town’s founders, poor but hopeful, were not welcome in Oklahoma’s successful black enclaves and so were forced to create their own community. But now their own mythology is collapsing under the weight people always place on history, as the young people grow disillusioned about the future and the elders (men especially) cling to the past. The prose is knotty and beautiful, like a storm-buffeted tree. Reading Morrison’s words made me feel inadequate, clumsily herding my facts and quotes and citations in ways that seemed entirely removed from the actual human truth of what it was to be a black person in Oklahoma in the age of Jim Crow.

I can’t tell that truth, not within the limits of journalism and nonfiction writing. I didn’t experience it, and when I talk to people who did, I can feel the chasm opening between us as they get transported back in time. In Tulsa there was a lovely amusement park once with cotton candy and bumper cars and a Ferris wheel that lit up the night sky; black people were only allowed to enter the park on Juneteenth. When I ask people about this place, I want them to tell me they refused to go out of principle, or that they were angry or embarrassed or ashamed--emotions I sometimes apply retroactively to experiences in white spaces during childhood that felt indescribably off, even during the moment. But no, riding the Ferris wheel was a joy for the little boys and girls of Greenwood; hearing their cries of delight was a joy for their parents. It didn’t matter that it was only for one day; what mattered was that they had the experience at all. I pose questions about the amusement park in a world where I get paid by white-owned corporations to criticize white power structures; Greenwood elders remember a world where such critiques were ignored at best, and were brutally lethal at worst--especially here in Tulsa. In Paradise, Morrison describes how a woman born in the 1920’s perceives a young man caught up in the Black Power movement of the 1970’s. “He talked about white people as though he had just discovered them,” she writes, “and seemed to think what he’d learned was news.”

Run It Back is a free newsletter about neglected black history. Sign up for new editions in your inbox right here.

As I plow forward in the Greenwood chronology, I can feel my mind loosening up. You have to be limber to write history. Journalism, the only form of writing I’ve really done for the last decade, is a rules-based enterprise. If enough experts or “authoritative” sources say something is true, you can run with it. If you’re tired or bored or overworked, it’s easy to follow the rules rather than try to figure out the truth. As a reporter reared in the age of aggregation, I’ve often been guilty of it.

But diving into history exposes all the blind spots in our attempts to make sense of the world--in old news articles presenting slanted objectivity, in oral histories that accidentally recount false memories and purposefully omit inconvenient facts. In names missing from city directories but present on census rolls, in land deeds that hide fraudulent schemes behind phrases like “twenty five dollars and other valuable considerations.” There is no such thing as an authoritative document, really. There are people crafting documents in order to assert their own authority over the world. I’m telling you, you have to be limber for this.

Run It Back adhered closely to the factual side of history-making in its initial run. I was learning the information as I shared it with you, and trying to shape it into a digestible format for both of our sakes. But in my manuscript, I’m now several decades ahead of where Run It Back left off in the Greenwood timeline in 1925. So I’ll continue to walk you through the history, but I’ll be leaning more into interpreting what certain events and documents might mean, and acknowledging when I don’t have all the answers. There are gaps in both my historical knowledge and in the historical record, contradictions that I need to work through as I race to finish my book next year. So this will be the space where I do that, filling in the gaps of my understanding when following the available facts leads to maddening dead ends, or sometimes, the shadows of uncomfortable truths.

I finally got over my frustration with writing yesterday by unplugging my router and turning off my phone, so I had to face my inner voice rather than the quippy, curated voices of social media. I thought less about what each individual fact I had gathered said, and more about what I wanted to say with them, collectively. I was no longer reciting a dry chronology or trying to speak in a voice that was not my own. I was creating something new, about the past but just as much about how the current moment shapes how I see those events. I can’t tell anyone else’s story; what a hubristic notion it was to ever think I could. I can only offer a view of Greenwood from my own vantage, and hopefully help others see that we’re all peering at the world that came before us more than a little askew.

Thanks for reading Run It Back. During 2021 and 2022 the newsletter will be focused on Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, which I’m currently writing a book about for Random House called Built From the Fire. You can catch up on the story so far right here. If you found this issue informative or enlightening, feel free to share it on social media.

if you you have comments, critiques, or tips that may help with my research, just reply directly to this email. I’ll be back with more reporting from Tulsa soon.

Starting with your piece on the ringer and every edition of this newsletter, you’ve educated a 32 year old white guy from Michigan on history he had no idea happened.(which truly says so much on what we learn in school) I’m happy to see the newsletter continuing and I’m excited for the book. What your doing matters and is important.

You write beautifully!