Learn the Story of Black Wall Street

This article chronicles the history of Tulsa's Greenwood district, from its origins as Native American land to its rebuilding after the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Welcome to Run It Back, my newsletter about neglected black history that still matters in today’s world. Read this short article to learn about the history of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, also known as Black Wall Street. Then sign up for the Run It Back newsletter to receive biweekly articles about black history, or check Built From the Fire, my expansive book on Greenwood’s history.

The Birth of Black Oklahoma

Black Oklahomans have lived just outside the frame of western myths for a long time. The first to move out west were the thousands of slaves who accompanied members of the Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole Tribes during the forced Native American removal to Oklahoma in the 1820’s and ‘30s. Enslaved people were forced to serve as hunters, nurses, and cooks throughout the brutal winter trip known as the Trail of Tears. After the Civil War, the slaves were freed and granted tribal citizenship. In the Creek and Seminole tribes, they farmed alongside Native Americans on communally owned land, served as Supreme Court justices in national governments, and acted as translators for tribal leaders in negotiations with U.S. officials.

A second group of blacks--”state Negroes,” they were sometimes called--were part of the settler mythology that birthed terms like “Sooner” and “Boomer.” De'Leslaine Davis, a South Carolina native, was one of the few black people to participate in the very first land run on April 22, 1889, when the U.S. government opened up Oklahoma Territory’s “Unassigned Lands” to outside settlement. In the coming years thousands of other African Americans would participate in later land runs, joining Davis as “settlers” in a region that was already filled with both indigenous and black residents. Black members of the tribes and the new black settlers often resented each other.

But white people, who were taking over the Twin Territories at an alarmingly fast rate, resented both groups more. When black tribal members were granted land allotments by the federal government along with their indigenous brethren, white con artists defrauded them of their land, purchasing huge tracts of black-owned property for less than $1 per acre. Meanwhile, as the Territories contemplated statehood, white politicians rejected efforts to make the new Oklahoma a symbol of racial equality and instead embraced a vicious Jim Crow regime. Black people--both tribal members and “state Negroes”--were banned from white schools, train cars, and even phone booths.

The Rise of Greenwood

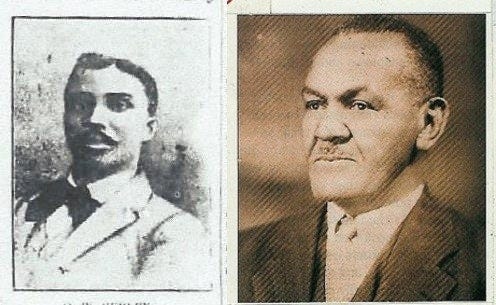

Amidst this dimming of opportunity out west, a new black community emerged on the northern edge of Tulsa. It was called Greenwood. Though popular myth says that Greenwood was a planned community, land records indicate that it emerged haphazardly over the course of about a decade and only slowly fell into black ownership. O.W. Gurley (pictured left above) was likely the first entrepreneur on Greenwood Avenue, opening his People’s Grocery Store there in 1905. Soon he was joined by entrepreneurs like J.B. Stradford (pictured right above), a real estate agent and lawyer, and Loula Williams, a theater and confectionery owner, among many others.

Greenwood attracted ambitious black people who knew that Oklahoma was rich with oil and that it had a number of all-black towns where black independence was celebrated. Oil ultimately played only a tertiary role in black success--black workers were systematically excluded from the oil fields. And while all-black towns were plentiful, Greenwood was ultimately still a neighborhood in Tulsa, and its destiny was deeply bound to the actions of white people south of the railroad tracks. But the spirit of independence that defined all black Oklahoma was alive and well there. Greenwood residents melded Booker T. Washington’s vision of by-your-own bootstraps black capitalism with W.E.B. Du Bois’ fierce calls for racial justice.

White Violence Grows

Outside the cocoon of Greenwood, Oklahoma was being wracked by racist whtie violence. In 1914, a 17-year-old black girl named Marie Scott was lynched in Wagoner, just 40 miles from Tulsa. Whte newspapers cheered the murder; Greenwood’s A.J. Smitherman, the fiery editor of the Tulsa Star, was one of the few public figures to speak out against it. Smitherman was a consistent and vocal opponent of mob law. He was not naive enough to assume that a trial for a black criminal suspect would be fair, but he understood that the elimination of even the pretense of justice would ultimately prove disastrous for his people. “These conditions are becoming very alarming and a serious calamity is sure to follow if something is not done to force all citizens to respect the law,” he wrote after Scott’s lynching.

But mob law spread like a disease across the entire nation. In 1919, during what came to be known as the Red Summer, race riots in more than 30 U.S. cities, from Washington D.C. to Brisbee, Arizona, seized the country. Hundreds of people were killed, most of them black, and thousands of homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed. A victim of one of these riots from East St. Louis, Illinois actually spoke in Greenwood in 1920 about all that he had seen.

The Massacre

An event as devastating as the Tulsa Race Massacre--thousands of homes destroyed, millions of dollars in damage accrued, potentially hundreds of lives lost--must be thought about on the scale of institutions, not individuals. But the inciting incident was an encounter between a pair of teenagers--Dick Rowland, a black shoe shine boy, and Sarah Page, a white elevator attendant. Rowland was arrested on a false rape charge on May 31, and black men in Greenwood, keenly aware of the history of lynching in thier own state and hometown, went to the courthouse armed and ready to protect him that evening.

An altercation broke out between the armed blacks and hundreds or thousands of whites who had gathered around the courthouse, likely to observe or participate in a potential lynching. Several people of both races were shot and killed in the streets of downtown Tulsa. Blacks retreated to Greenwood; whites broke into armories and hardware stores seeking weapons. They were preparing for something more.

The police and National Guard, which were called in late into the night to bring order to the chaos, empowered a white mob to lay siege to Greenwood rather than protecting the neighborhood. J.M. Adkison, Tulsa’s police commissioner later estimated that 400 men were deputized on the night of the massacre. He even admitted that many men did not even have to provide their names to earn a commission. Adkison would later be identified as a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

On the morning of June 1, 1921, at the sound of a clear whistle, a mob of whites estimated to be in the thousands crossed the railroad tracks that divided white and black Tulsa. They shot innocents, burned down buildings, and terrorized black individuals. More than 1,200 homes were destroyed and the entire central business district was destroyed. An unknown number of people were killed, but estimates reach as high as 300. The losses were, in many ways, incalculable.

How They Rebuilt

After the massacre, tents stretched across the burned-out prairieland for months. Though city leaders said they intended to rush to Greenwood’s aid, that never happened. Instead, Merritt J. Glass--another Klan member--launched a scheme to try to relocate blacks farther north in order to convert Greenwood into a train depot. Greenwood’s sharpest business and legal minds resisted the effort.

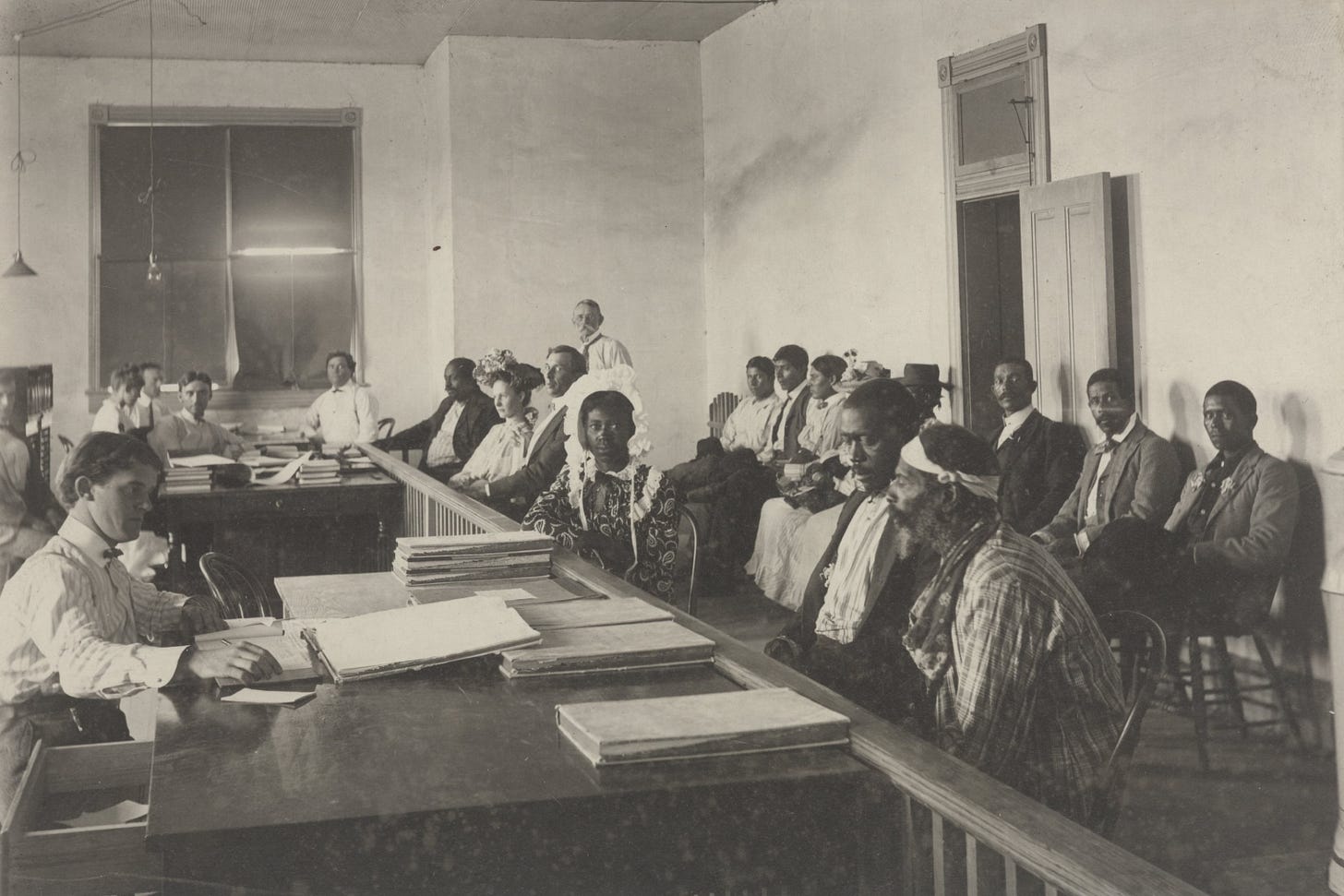

Help came from black donors in other cities, the Red Cross, and Greenwood residents’ own determination to rebuild. At the Red Cross relief headquarters set up in the neighborhood, sewing machines whirred as black women and girls were tasked with making clothes and bedding to replace all that had been burned by the white mob. Families banded together to build new homes with donated lumber. Many who had cobbled together somewhat comfortable lives in the heart of a Jim Crow regime were forced to live without heat, electricity and running water for months or even years.

But the residents of Greenwood were tenacious, and by 1925 they were prepared to show the world how far they had come from disaster.

Read more about how the origins of Greenwood, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the community’s astonishing rebirth in my narrative nonfiction book Built From the Fire. The book was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and the Washington Post, and it has been named a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, among other awards. Buy Built From the Fire on Amazon, Bookshop, or at your local bookseller.

Photos courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society, Greenwood Cultural Center, and Wikimedia Commons. Sources available on individual issues of Run It Back.

Excellent article. My great grandfather was born on the Cherokee rez and orphaned when whites killed his parents. He later married a Black woman from Utah and moved out of Oklahoma around the time of the Osage murders and things getting hot in Tulsa. He hid in the Black community in Utah so his kids weren't taken from him for the Indian board schools. A lot you have here is similar to stories I heard from my grandparents. Thanks for bringing this and more info to the light

Good Read, thank you! I look forward to going through all your stories.

Nice mention about Bisbee AZ... I teach an AZ history class and one of the best/worst stories from that town is about a Labor Strike wherein the local law and "reputable businessmen" forcibly loaded up train-cars full of workers (who were striking due to insane mine work conditions) and shipped them out into the middle of the NM desert and left them there. 1917, wtf?!