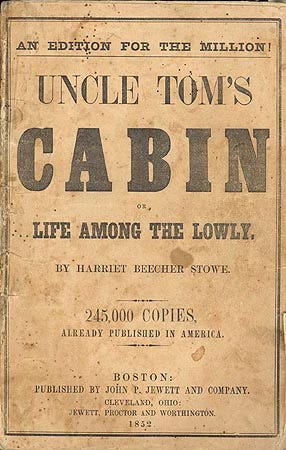

An 1853 edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, printed after the book had become a national phenomenon

They said the book was poison. When Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was first published in 1852, the white Southern response was “nearly all outrage and invective,” according to the scholar Thomas Gossett. In Mobile, Alabama, vigilantes forced a bookseller to flee town after he featured the antislavery novel in his shop. At the University of Virginia, the book was burned on campus.1 In Maryland a free black man named Samuel Green was sentenced to ten years in prison for possessing the book, which was labeled “an abolition pamphlet…calculated to create discontent amongst the colored population.”2

Fueling the anger was fear. In the arguments over slavery, Southern slaveowners had custom and the law on their side. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, however, reset the terms of the debate. Here was a work that humanized enslaved people and illustrated the horrors slavery had wrought, while filtering its abolitionist argument through the lens of the Great American Novel. The slaveowners may have had Southern politicians and police patrols in their back pocket, but art and culture were harder to control.

In the Southern white press, critics catastrophized about the impact Stowe’s work would have on the white youth, the generation expected to uphold the nation’s darkest institution. "On every drawing room table of the North will be found engravings…illustrating Uncle Tom's Cabin, or the horrors of slavery,” read one editorial in an Alabama newspaper. “Over these pictures the children will cluster [in the] evenings, their innocent and tender minds drinking in the poison, while their parents are perhaps deep in some abolition speech work.”3

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was popular, accessible, and winding its way toward young people. That made it dangerous.

----

Since the murder of George Floyd in 2020, black history has been in sharp focus in America. Horrific events like the Tulsa Race Massacre reached unprecedented national prominence, while Juneteenth is now at least widely acknowledged, if not exactly widely celebrated. As I spoke at colleges, bookstores and book festivals on my book tour for Built From the Fire last year, I met people of all ages and backgrounds in every corner of the country. They all wanted to know more.

I spoke at at 15 colleges during the 2023-2024 school year about the history of Greenwood and my approach to writing and research. Here’s me at the University of Alabama with a journalism class and my old mentor, George Daniels.

But there’s been a bitter retrenchment from this history as well. Sixteen states have enacted anti-“critical race theory” legislation since 2021, and eight states have passed laws eliminating diversity, equity and inclusion offices from colleges. Three states are now denying college credit for AP African American Studies courses. This is as much about delegitimizing the work of largely black scholars and administrators as it is about shielding children from honest lessons about the legacy of race in America. The paranoia that led to the demonizing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin has returned in full force, sometimes with chillingly similar arguments--recall the controversy in Florida when the Board of Education adopted new lesson standards teaching that slaves adopted skills “for their personal benefit” while in bondage.

Telling the truth about what happened in our country matters. It is not only because public policy debates regarding reparations and interstate removal plans are being shaped by interpretations of the past. It is not only because of the old “history repeats itself” maxim, which is more true than I gave it credit for as a kid. History expands our boundaries for what is possible, even as politicians try to herd us into a claustrophobic societal pen. When you learn that there were black people in my home state of Alabama who owned slaves in the 1800’s and others who were members of the Communist Party in the 1900’s, it begins to explode any idea of racial stereotype. Our humanity is expanded through these narratives--sometimes the revelations are heartening, other times harrowing. But better to be a person than a political prop.

Starting today, this newsletter is expanding its remit. Old heads know that the vast majority of the stories on Run It Back have been about expanding that possibility space in the world of black Oklahoma--writing about black cowboys, entrepreneurs, gambling kingpins, would-be oil tycoons, and the many victims of racial violence. Going forward, I’ll cast an eye all around the country for more black narratives that extend beyond our usual historical staging grounds, the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement. I want to help fill in the gaps in our story that so often don’t make it into school curricula or popular culture.

I also want to make sure everything isn’t about trauma and the brutalities of racism. While interest in learning and teaching black history is rising, researchers at the John Hopkins Institute for Education Policy have found that these lessons dwell too much on the negative, often ignoring black achievement. A 2014 paper published in the Journal of Black Studies found that knowledge of black history correlates positively with self-esteem among black youth. Black people have accomplished quite a bit in our time on these shores; it’s vital we learn more of those stories too.

A recent talk I gave at the St. Louis Public Library, where I was interviewed by Missouri Historical Society President Jody Sowell

I need help to execute this vision, so I’d like you to consider buying a paid subscription to Run It Back. Here are the different ways you can contribute:

A monthly subscription is $6 per month

An annual subscription is $60 per year

You can contribute a larger amount of your choosing by signing up as a “Patron of History”

For the first 100 people who get an annual subscription or a Patron of History subscription, I’ll mail you a signed copy of the new paperback edition of Built From the Fire, personalized to your liking. Or I can gift you (or the person of your choosing) an audiobook copy via Audible if you prefer. When you subscribe, I’ll follow up via email to work out the particulars.

Even though I’m offering paid subscriptions for the first time, all the articles on Run It Back will remain free. I’m experimenting with a completely voluntary patron model so that this work can be widely available. My work could be of great use to teachers who are trying to include more black history lessons but need material that is accurate, evocatively written, and opens up space for intellectual discussion and debate. I strive to achieve all these things with my work. Please check out the new Education section of the Run It Back website, which organizes the archival issues by topic and provides PDF versions of all the articles to make easy classroom handouts.

I’ll be updating the newsletter every other week from now on, as I did when Run It Back first launched. The pieces will be a mix of deeply researched historical narratives, essays reflecting on my approach to chronicling history, and some insight on my writing and research techniques as a budding historian. I’ll value impactful brevity (1,500 words or less per article) over sprawl. Expect more pieces that use moments in the past to shed light on what’s happening in our country today. I’m really excited about a series on the history of the black vote that I plan to run throughout the fall.

You don’t have to pay me a dime, but the money will help me continue to share my work in this format instead of hoarding it in books or on paywalled news websites. As an aging millennial (shudders) I have a soft spot for the open, collaborative internet of my teenage years. And I have big ambitions for Run It Back; the more folks that support this project, the easier it is to focus on this writing venue.

Thank you for reading, sharing, and subscribing. I hope to continue writing about black history for a long time to come.

Sources

Thomas F. Gossett, Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press), 210-11.

David Armenia, “Samuel Green (b. 1802 - d. 1877),” Archives of Maryland, https://tinyurl.com/yrb34vvp

“The Slavery Agitation—Its Philosophy,” Jacksonville Republican, Oct. 26, 1852, 1.

Count me in! Thanks for sharing all your hard work and well-crafted posts, Victor. It's been eye-opening and really look forward to reading more.

Love this, Victor! And as soon as I have some money, I will contribute. Promise. I did all I could to get your book reviewed, just wasn’t enough. Big fan!