Freedom by Violent Means: Part I

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 sparked a wave of violent resistance, leading to a killing in Christiana, Pennsylvania

Run It Back offers carefully researched articles on lesser told parts of black history. But I’m only able to do this work with your help. Please consider getting a paid subscription to Run It Back to help me keep writing these stories and making them widely available to students, educators and lifelong learners.

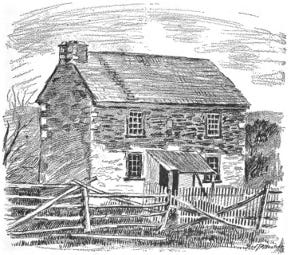

William Parker’s house was the closest thing the black people of Christiana, Pennsylvania had to a fortress. The two-story stone structure was nestled in a thicket of trees and commanded a half mile berth from the nearest neighbor–“almost invisible to the outside world,” one observer noted. A horn in the attic served as a call-to-arms. If a neighbor heard the horn, they knew to grab the closest gun or corn-cutter and head to the Parker house to defend against whatever enemy had punctured the community’s tenuous peace. On Sept. 11, 1865, that enemy was a posse of Maryland slavecatchers.1

Edward Gorsuch, a farmer from Baltimore County, Maryland, had been after four of his former slaves for the better part of two years, since they walked off his property with five bushels of stolen wheat and their freedom in the fall of 1849. He had enlisted the aid of his son, a few hometown friends, and most critically, a United States Deputy Marshal named Henry Kline. Even for the era, Gorsuch’s pursuit was unusually dogged. But he was empowered by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which vastly expanded the capacity of enslavers to reach into the supposedly free states of the North and snatch human beings back into the jaws of servitude.2

Gorsuch had tracked his former slaves 60 miles, right to Parker’s stone house. His intel was sound–two of them, Nelson Ford and Joshua Hammond, were both inside the home with Parker and his family. But an agent of the Underground Railroad had tipped Parker off earlier in the week that Gorsuch’s posse was snooping around Christiana. The runaway slaves had come to Parker’s fortress seeking protection. While Gorsuch had planned a surprise ambush, it seemed more likely that he was stumbling into a trap.3

Still, he thought, he had the law on his side, both in theory and in flesh. As the slavecatchers prowled around the outside of the stone house, Kline, the U.S. deputy marshal, read out the warrants a federally appointed commissioner had issued for the seizure of the four black men. “We are commanded to take you, dead or alive,” Kline said, “so you may as well give up at once.”4

Parker was unfazed; he had faced off against slavecatchers before. He dared the men to enter his home and come up the narrow staircase to try to take the two men by force. Or perhaps, he mused, they’d like to survey the livestock in his barn. They were more likely to find stolen property there than amongst a room full of black folks.

Kline and Gorsuch tired of Parker’s taunts. Kline instructed one of the men in the posse to start gathering hay to scatter across the base of the stone house. They’d burn the Negroes out if they had to.

Parker’s wife Eliza dashed up to the attic to reach the horn. Perching in the window sill, she blew a note that perked the ears of free black people for miles around and cooled the blood of the slavecatchers at the front gates. Two of the white men scrambled up into an orchard by the house and fired at Eliza’s window, but their aim was wide. She blew the alarm again, and again.5

The slavecatchers grew nervous. Gorsuch’s son Dickinson wanted to retreat. Even the deputy marshal figured they could come back later with a greater show of police force–they were within their legal right, after all–and get the Negroes to stand down.6

But Gorsuch refused to budge. While he had considered himself a benevolent enslaver when his colored people were meek and kind, he could spare them no sympathy after the niggers ran away. He wouldn’t leave until the proper balance had been restored–not only on his financial ledger but in the social order he was bent on upholding. “I want my property,” he declared, “and I will have it.”7

—

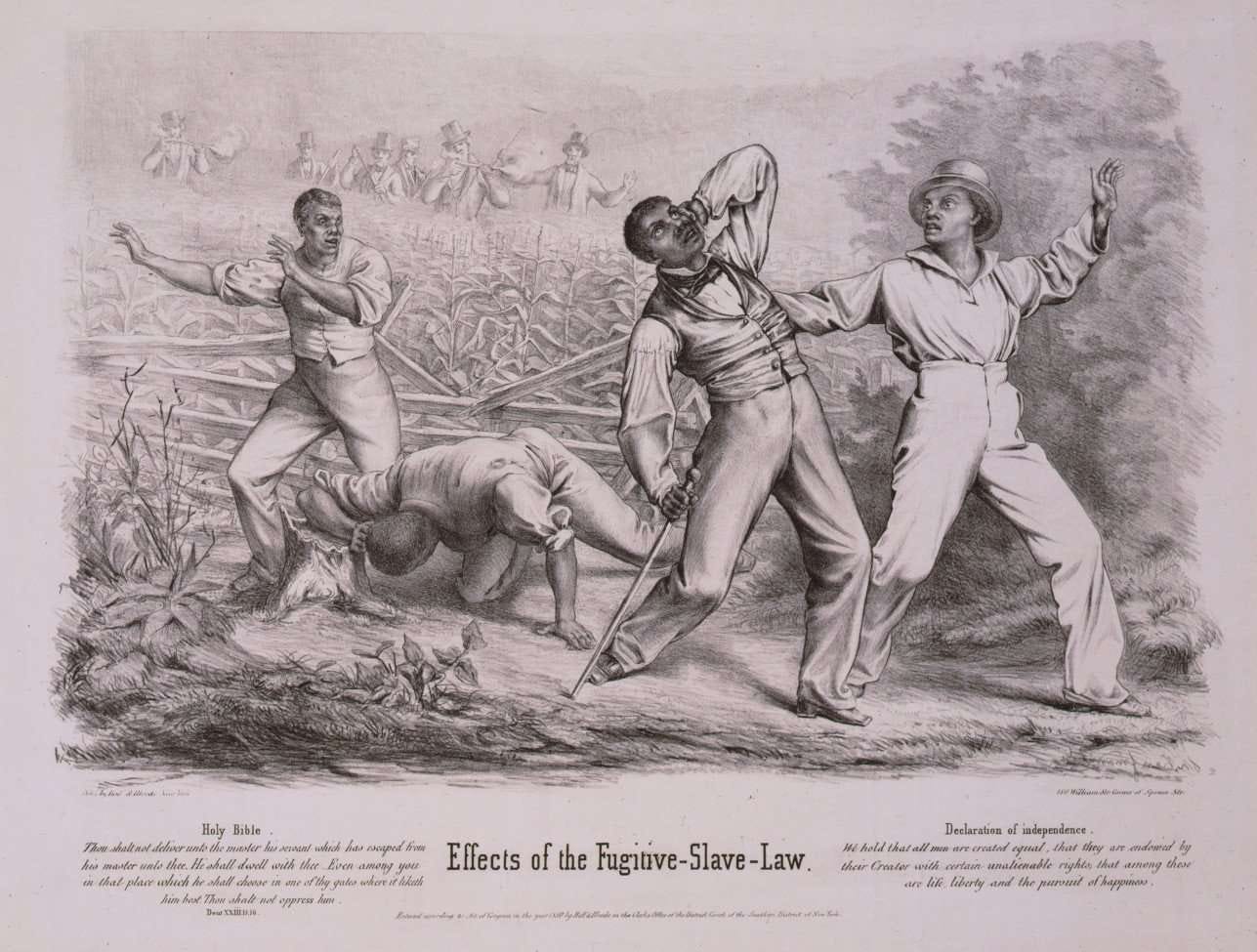

Sometimes in America, a law is so heinous that its passage becomes a radicalizing event. Injustices that had felt like abstractions of evil become concrete as the machinery of enforcement whirs into action. Victims transform from demographic groups to names to neighbors. Indifference mutates from a numbing sedative to a needle lodged in the back of your mind–the pain of a moral prick without the release of an opiate. This was the fallout of the Fugitive Slave Act, which helped propel the nation on the path toward civil war.

The act was the most controversial piece of the Compromise of 1850, a bundle of Congressional laws that sought to placate the South by cementing slavery’s place in the Union. Under the Fugitive Slave Act, a slaveowner could venture to a free state and claim an alleged runaway slave as his property with no documentation beyond his own testimony. The slaveowner had the right to enlist U.S. marshals, their deputies, and local citizens in his slavecatching posse; anyone who refused to help could be accused of helping the fugitive and face a fine of up to $1,000 or jail time. Once the black person was apprehended, they were subject to a hearing where they could not testify on their own behalf. A federal commissioner would decide their fate, though this official would receive a payment twice as high if they ruled in favor of the slaveowner rather than the alleged slave. More than 80 percent of fugitive slave hearings ultimately ended with black people being shipped south into bondage.8

While many Northerners initially expressed support or indifference toward the law, sentiment turned against it as it was put into practice. One black man accused of being a fugitive in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania was killed by a pair of U.S. deputy marshals who were trying to apprehend him. A pair of black parents were shipped back to the South by the courts, leaving their youngest child, born free in Pennsylvania, an orphan.9 Horror stories filled newspaper pages, but more importantly, touched individual communities. The entire fugitive slave-catching system, Frederick Douglass once remarked, allowed slavery to be “nationalized in its most horrible and revolting form.”10

A violent strain of resistance quickly formed against the law, and William Parker became one of its most effective adherents. Born a slave in Maryland around 1821, he ran away to freedom at the age of 16 after getting into a scuffle with his enslaver, who was trying to beat him with a stick (“My rights as a freeman were secured by my own right arm,” he later wrote). Parker continued to match force with force; he moved to Lancaster County in Pennsylvania and led a mutual-protection society for black people. Their mission was combating slave catchers and their allies by any means. Sometimes that meant violent standoffs with the Gap Gang, a group of white ruffians who functioned as slave bounty hunters in the region. Other times it meant beating or threatening fellow black residents they discovered had been aiding the slavecatchers.11

The notion that the issue of slavery might be solved through politics or compromise did not figure in Parker’s calculus; even for a free black man in a supposedly free state, life was about survival. “The laws for personal protection are not made for us, and we are not bound to obey them,” he once explained to a white neighbor. “If a fight occurs I want the whites to keep away. They have a country and may obey the laws. But we have no country.”12

Parker was widely beloved, respected, and feared in Christiana by the fall of 1851, but Edward Gorsuch knew nothing of the man whose home he had come to raid. Gorsuch, about 53 years old and reared in a slave society, imagined black people to be docile and eager to submit to authority. His runaway slaves were less people to him than confused pets. He seemed convinced they would prefer life on his farm than whatever hold on independence they’d carved out for themselves here in the Pennsylvania wilderness.13

The sound of the horn should have been the last signal he needed that this wasn’t the case.

Within half an hour of Parker’s wife sounding the alarm, roughly 100 black men and women emerged from the thicket of the woods. They carried pistols, hunting rifles, scythes, rocks–whatever tool might come in handy. A couple of white neighbors also appeared; they weren’t part of the black mutual-protection group, but they also refused to follow the letter of the Fugitive Slave Law when Gorsuch and Kline asked them for help apprehending the runaways. “You need not come here to make arrests,” Castner Hanway, one of the white men, said to the deputy marshal. “You cannot do it.”14

But finally Gorsuch saw him–Joshua Hammond, one of the slaves he was looking for. Gorsuch had described him as “well grown” in the legal documents he filed seeking Joshua’s apprehension. He simply couldn’t understand why the slave had run away. He even planned to free Joshua–one day.15

But Joshua had changed his name to Samuel Thompson after his escape. The young slave from Gorsuch’s farm and the free man now standing in William Parker’s front yard were different people. Thompson looked at his former enslaver. “Old man, you had better go home to Maryland,” he said.

“You had better give up,” Gorsuch replied, “and come home with me.”16

Go home. Come home.

Thompson grabbed a pistol that a friend nearby was holding and clubbed Gorsuch in the head. Gorsuch fell to his knees. He tried to rise, but Thompson clubbed him again. Then he fired a bullet into Gorsuch at point-blank range.17

More gunshots followed, echoing through the forest in the morning gloom. The accusations of treason and calls for hangings would soon echo louder. But there was a quiet tragedy in that moment before the bang, when the man seeking freedom asked his former captor to abandon this doomed mission, and the captor still could not fathom that the man he saw as a dog might actually bite him.

Part II of this series will be published the week of Oct. 6.

Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North (Oxford University Press, 1994).

Ibid.; Anthony Rice, “A Legacy Transformed: The Christiana Riot in Historical Memory” (PhD diss., Lehigh University, 2012).

Bloody Dawn.

William Parker, “The Freedman’s Story,” The Atlantic, Feb. 1866.

Ibid.

Bloody Dawn.

Ibid.; “The Freedman’s Story.”

Liz Tracey, “The Fugitive Slave Act: Annotated,” JSTOR Daily, May 19, 2025; Jayme A Sokolow, “The Jerry McHenry Rescue and the Growth of Northern Antislavery Sentiment during the 1850s,” Journal of American Studies 16, no. 3 (1982): 427–45.

Gerald G Eggert, “The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg: A Case Study,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 109, no. 4 (1985): 537–69.

“The Fugitive Slave Act: Annotated.”

Bloody Dawn.

Ibid.

Ibid.; “A Legacy Transformed.”

Bloody Dawn.

Ibid.; “Edward Gorsuch,” Maryland State Archives.

Bloody Dawn; “The Freedman’s Story.”

Bloody Dawn.

Thank you for shining a light on this troubled moment in our history…and the heroic response to it from some. I look forward to part 2.