Truthtelling in a Time of Lies

William Still, a conductor on the Underground Railroad, gave fugitive slaves the space to tell their own authentic stories

Run It Back offers carefully researched articles on lesser told parts of black history. But I’m only able to do this work with your help. Please consider getting a paid subscription to Run It Back to help me keep writing these stories and making them widely available to students, educators and lifelong learners

William Still was a meticulous man, as careful with facts and figures as he was with the people placed under his protection. When fugitive slaves made it to Philadelphia on their way to freedom, Still’s office at the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society was often their first stop (if he did not meet them at the train station when they arrived). He and his wife Letitia opened their home to freedom-seekers even as slavecatchers prowled the city’s streets. If a runaway slave needed a train ticket for the next leg of their trip, or a haircut to better blend in with black Northerners, Still and his cadre of abolitionist allies would pay for it. Everything was documented, down to the date and penny, in Still’s copious notes, along with newspaper clippings, interviews he conducted with the fugitive slaves, and letters from those who had continued on past Philadelphia to find opportunity elsewhere. He brought form and order to a decentralized network that had no president, no balance sheet, and no official headquarters.1

“Nobody professed to own the Underground Railroad," Still reflected later.2 True. But Still was the closest thing the Underground Railroad had to an accountant, and later, a historian. His work–and especially the book he would eventually publish–allowed fugitive slaves to have the final word on what they experienced, rather than letting slaveowners and their political allies craft a false national memory of enslavement.

Born free in 1821 to parents who had escaped slavery, Still moved to Philadelphia as a young man in the early 1840’s. He worked odd jobs as a brickyard laborer and a domestic servant but longed for a role that would expand his intellect. In 1847, he landed a position at the offices of the Pennsylvania Anti Slavery Society, an abolitionist group that sought equality for black Americans. Still was hired as a clerk. His mostly mundane duties included cleaning the office and reading the mail. But he was smart, savvy, and almost religiously focused on work. Soon enough he’d play a central role in the organization.3

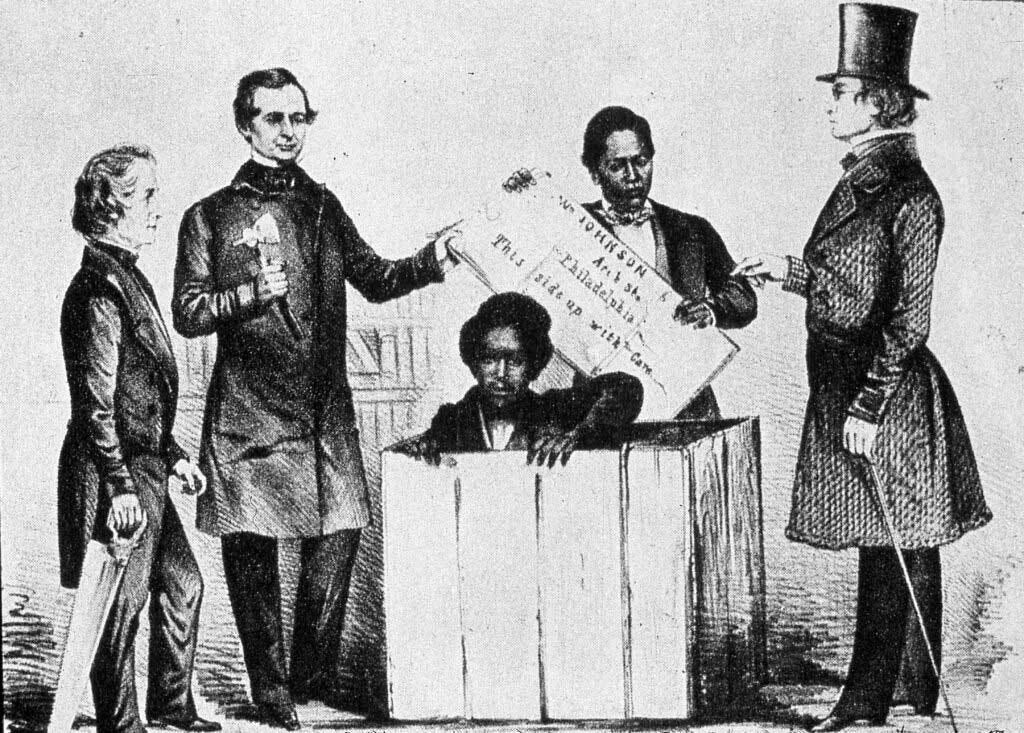

The Anti Slavery Society office, located a couple of blocks from Independence Hall, became the “unofficial headquarters for Philadelphia’s Underground Railroad,” according to historian Andrew K. Diemer in his book Vigilance. The organization had a network of agents in nearby cities like Wilmington, Delaware and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania who ushered runaways to Philadelphia by train. Still and his boss James McKim would then help them continue on their journey northward, often to Canada. Still was present in the office on the day in 1849 when a large freight package arrived containing a human being–Henry “Box” Brown, who famously escaped his enslaver by shipping himself north via steamboat, train, and wagon. Still appears in a famous lithograph that depicts the moment abolitionists removed the lid from Brown’s crate.4

By the early 1850’s, Still was regularly assisting McKim with his key duties, such as editing the abolitionist newspaper The Pennsylvania Freeman and coordinating arrivals of runaway slaves. But he also realized that the Anti-Slavery Society did not have the means to help all the people that were coming through its doors. Many leading white abolitionists of the era saw the Underground Railroad as secondary to the larger mission of toppling the institution of slavery through political and economic means.5 But Still saw these brave individuals who traveled the Railroad’s dangerous routes as symbols of hope, representing the best of his people. ”They were determined to have liberty even at the cost of life,” he wrote.6 Still understood that these individual acts of defiance could collectively spell slavery’s doom.

In 1852, Still and several other abolitionists revived an independent group called the Vigilance Committee, which first started aiding runaway slaves in the 1830’s. Robert Purvis, the son-in-law of Philadelphia entrepreneur James Forten, led the organization. Still was named secretary, tasked with keeping the committee’s finances in order and documenting its activities. It was through this organization that Still began taking detailed notes of his every interaction with the fugitive slaves that he aided.7

Still had another motivation for chronicling the lives of runaway slaves. One day in 1850, while he was working at the Anti-Slavery Office, an anxious man named Peter walked through the front door. He had fled a plantation in Alabama and was seeking his parents, who he had been separated from as an enslaved child. Still was shocked; he realized Peter was his long-lost brother, who their mother had been mourning for decades. Still coordinated a heartfelt reunion between Peter and their mother in New Jersey. The experience inspired him to document all he could about the fugitives he encountered, in hopes that they too might one day be reconnected with lost relatives.8

—

After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, Still remained committed to fighting for black equality. He railed against Philadelphia’s segregated street cars and helped compel the Pennsylvania state legislature to pass a law desegregating them in 1867. He also became a successful businessman, operating a thriving coal plant and launching himself into Philadelphia’s black elite.9

But the work of his abolitionist days wasn’t over. Not long after the desegregation fight, he wrote to his daughter that he wanted to publish a comprehensive history of the Underground Railroad. The book would be modeled after The History of England, the nonfiction epic by British writer Lord Macalauy that used novelistic techniques to enrapture readers. Still would provide a similarly sweeping tale of black resistance in antebellum America, relying mostly on his careful records from the Vigilance Committee.10 The work felt urgent; white Southerners were already rewriting the story of the Civil War. Virginia author Edward A. Pollard coined the term “The Lost Cause" in his popular 1866 book defending the “nobility” of Southern slave society.11

Still “crashed” the book, to borrow a term from modern publishing. He wrote from five in the morning to eleven at night, producing about four pages each day. William Henry Furness, a prominent white clergyman, offered editing help.12 The book was anchored by vignettes of people who had made novel and daring escapes that attracted national attention, like Henry Box Brown or Ellen Craft, the black woman who posed as a white man to ferry herself and her enslaved husband to freedom. But the most affecting portions of the book to me were the small stories of largely anonymous black people who insisted upon liberty. A man from Delaware who escaped after his enslaver had threatened to wade “up to his knees in his blood.” A woman from Maryland who said if white folks caught a slave reading where she was from, they would “almost cut your throat.” A man from Alabama who hitched perilous rides atop northern-bound train cars during the night.13 All of them made it out, their stories rendered immortal through Still’s chronicle.

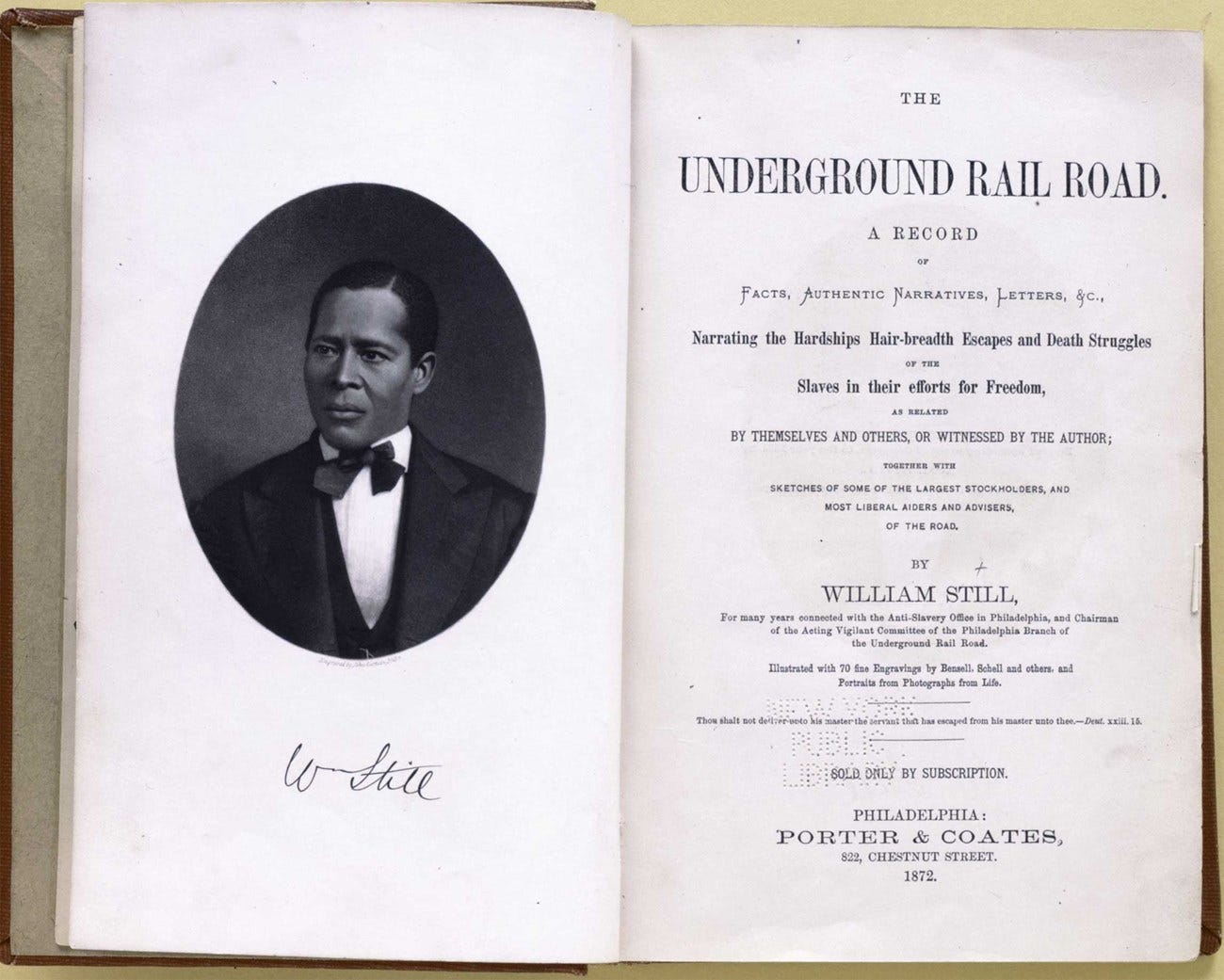

The Underground Railroad was published in 1872 in Philadelphia. At more than 700 pages, the tome was pitched as “an authentic history of a remarkable organization” in advertisements.14 Like any determined author, Still did a lot of self-promotion. He hired a team of sales agents, both black and white, to distribute the book. Through their network he reached readers in Georgia, California, and every corner of America in between. By the end of the decade, the book had sold between 5,000 and 10,000 copies.15 It was no Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the bestseller list, but it was enough to ensure that Still’s work would not be forgotten.

William Still understood that the slavery’s memory would be framed by the recorders of history. The abolitionists like him, who owned newspapers and thriving businesses, would inevitably get their due–especially his white peers. But it was the slaves themselves who risked becoming invisible in their own story, viewed as a backdrop for war or political theater rather than individuals who’d suffered the gravest atrocities and persevered. Still’s mission, he wrote, was “not for the purpose of amusing the reader, but to show what efforts were made and what success was gained for Freedom under difficulties.”16

More than anything, Still wanted to give the enslaved a voice. Their testimonials are his legacy.

Kriska Desir contributed to this report.

Andrew K. Diemer, Vigilance: The Life of William Still, Father of the Underground Rariload (New York: Penguin Random House, 2022).

“Underground Railroad,” The Star and Sentinel, May 13, 1870, p. 1.

Vigilance.

Ibid.; Hollis Robbins, “Fugitive Mail: The Deliverance of Henry ‘Box’ Brown and Antebellum Postal Politics,” American Studies 50, no. 1/2 (2009): 5–25.

Vigilance.

William Still, The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia, PA: Porter & Coates, 1872), p. 2

Vigilance.

Ibid.; Andrew Diemer, “The Forgotten Father of the Underground Railroad,” Smithsonian Magazine, Nov. 9, 2022.

Vigilance.

Ibid.

Jack P. Maddex, “Pollard’s The Lost Cause Regained: A Mask for Southern Accommodation,” The Journal of Southern History 40, no. 4 (1974): 595–612.

Vigilance.

The Underground Railroad.

The Independent, March 28, 1872, p. 6.

Vigilance.

The Underground Railroad.

Dear Doctor Luckerson, You hooked me with your first newsletters as you researched Built from the Fire and now as you further expand upon your exploration of our nation's history telling the stories we all need to know, but never learned in school, your research, once again, shines a light and kindles HOPE. Thank you for your research and writing.

I plan to read this now.

While in San Francisco this summer, I happened across a memorial plaque to Mary Ellen Pleasant. It is SF's smallest city park, consisting of the plaque in the sidewalk and six eucalyptus trees. I came to learn that she operated the California end of the Underground Railroad. I'd never thought of the railroad's running West. She was also a self-made multimillionaire.