The Story of Black Wall Street: A Way With Words

Black-owned media outlets were burned to the ground in the Tulsa Race Massacre. White outlets got the chance to write--and then almost erase--the first draft of history.

Download PDF version for the classroom

Words are weapons of liberation. This is a core thesis of the American project, which is why so much time in history classes is spent learning about famous documents and speeches. Many of the phrases known to every citizen--“All men are created equal,” “There is nothing to fear but fear itself,” “I have a dream”--are bound up in the idea of freedom. When they soar into immortality, they help an idealized version of our nation live on forever.

But in the muck of everyday life, the written word has tended to serve a different purpose. In white-owned newspapers, such as the Tulsa Tribune, language was a tool of oppression. Individual black people were lumped together as “Negroes,” or labeled worse when the paper stopped feigning politeness. Greenwood became “Little Africa” or occasionally “Niggertown.” The Tribune reported every criminal act by a black suspect it could uncover, while ignoring the many black success stories. Over the course of years, these daily words dulled the collective white conscience. Worse, when accusations of especially brutal crimes were leveled against black people, white newspapers were happy to condone lynch mob violence (I’ve previously written about newspapers endorsing lynchings in both Tulsa and Wagoner, Oklahoma). The Tribune was not uniquely vindictive--it was typical of the white journalism of the era.

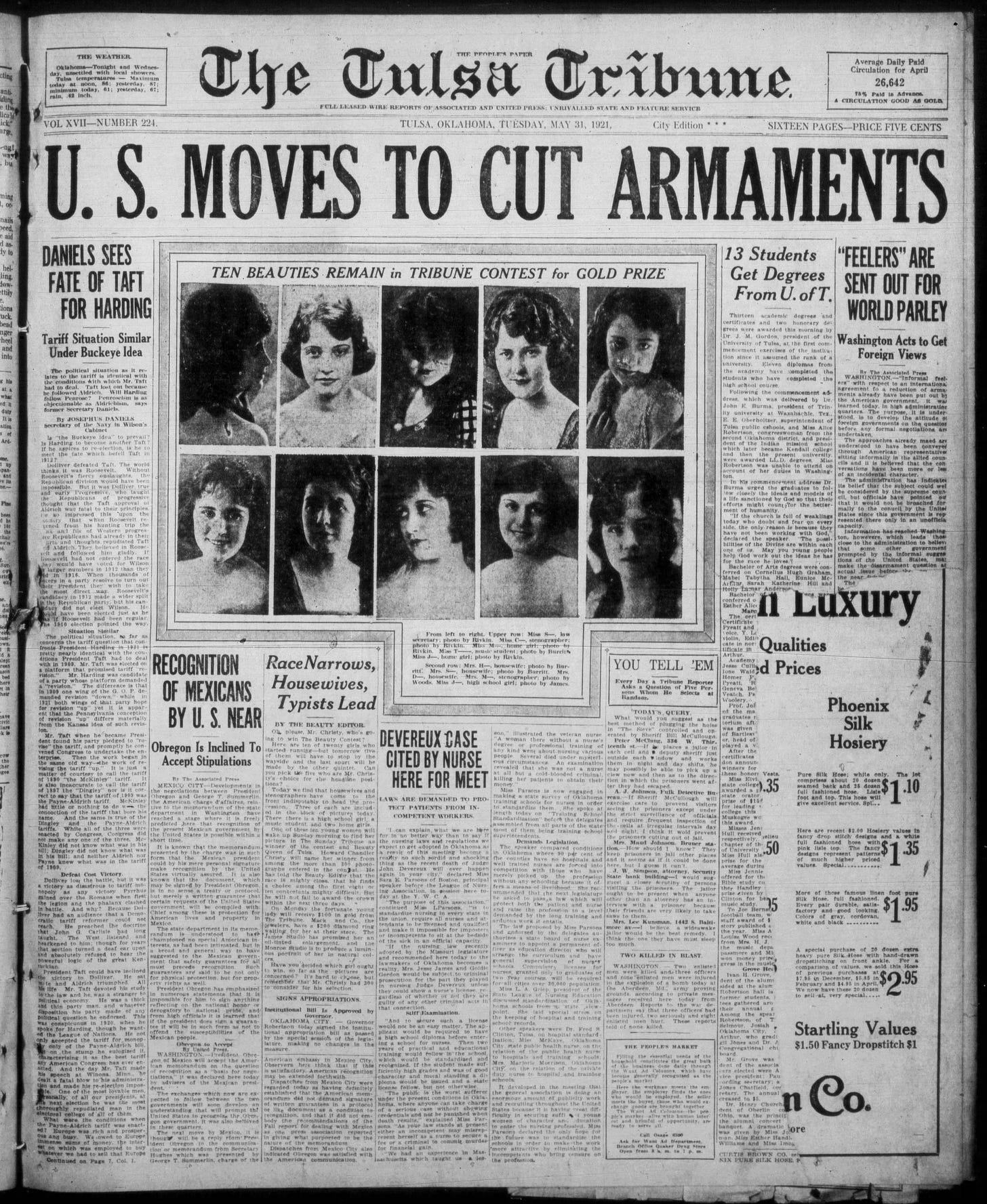

Because newspapers write the first draft of history, vast swaths of America’s past have been filtered through this racist lens. This plain fact is invisible to the average person by the time capital-H “History” has been distilled into a digestible form in a textbook or documentary. But in Tulsa, on May 31, 1921, the casual racism of the white press could no longer hide in the background. It became part of that capital-H History. And it started with a small news item on the front page of the Tulsa Tribune, titled “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator.”

This was the story of Dick Rowand and Sarah Page’s mysterious elevator encounter, doctored up for maximum titillation. The article read in part:

“A negro delivery boy who gave his name to the public as ‘Diamond Dick’ but who has been identified as Dick Rowland, was arrested on South Greenwood avenue...charged with attempting to assault the 17-year-old white elevator girl in the Drexel building early yesterday...He entered the elevator she claimed, and attacked her, scratching her hands and face and tearing her clothes. Her screams brought a clerk from Renberg’s store to her assistance and the negro fled.”

Where the Tribune sourced these details is unclear. They may have come from Page herself, a police account of what Page told authorities, or some combination of the two. The Tulsa World, which was generally less sensational than the Tribune, did not report on the incident until after the massacre, quoting a Tulsa police detective who called the initial account “colored and untrue.” The charges against Rowland were ultimately dropped, and the two teenagers both disappeared from the historical record almost immediately. In short, there is no evidence beyond the Tribune’s reporting that Dick Rowland actually attacked Sarah Page.

But the impact of the article was immediate. White people read it and saw reason to gather by the hundreds at the county courthouse, where Rowland was being held. Black people read it and saw reason to go to the courthouse in order to protect Rowland from an assumed white lynch mob. Without a dubious article to help spread rumors at warp speed through both communities, the initial altercation at the courthouse may never have happened (for more on how the sequence of events unfolded, read this timeline of the massacre in the Tulsa World).

The Tribune’s role in stoking the massacre is infamous for a second, stranger reason. For decades there has been a claim supported by eye witnesses that the Tribune published an even more inflammatory article called “To Lynch a Negro Tonight” in a late May 31 edition of the paper, explicitly calling for Dick Rowland’s murder. The article has never been found. However, the editorial page of the paper where it might have been located was ripped out of the edition that the Tribune kept on file, along with the “Nab Negro” article on the front page. The only reason we even know the front page article existed is because it was reprinted in other newspapers.

The front page of the Tulsa Tribune from the Tribune’s microfilmed archives, with the “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator” article ripped out. Half of the editorial page was also ripped out.

Historians and journalists have spent countless hours searching for this second article, seeking a smoking gun to prove a widespread conspiracy among Tulsa’s white elite. Strangers have contacted me seeking out the article this year, and a man observing Tulsa’s mass graves search this summer attracted a gaggle of reporters when he said may have laid eyes on the mysterious editorial. At this point it will likely be impossible to ever prove the article existed, and it’s easy to imagine people conflating the curious “Nab Negro” phrasing of the initial article with a direct call for a lynching decades after the fact.

For me and my work, the “missing” editorial is a distraction. I’m not interested in explaining a point in time, but a system of discrimination that recurs across generations. There is no outlier fact that can suddenly explain the reasoning behind the Tulsa Race Massacre, because it was not an outlier event. It was the result of a culture that Tulsa, and America at large, had been cultivating over the course of generations.

In the days following the massacre, the Tribune would quickly begin to rationalize the devastation as a comeuppance for violent blacks who, essentially, had it coming. In a June 4 editorial the newspaper wrote:

"In this old nigger town there were a lot of bad niggers and a bad nigger is about the lowest thing that walks on two feet. Give a bad nigger his booze, his dope, and a gun and he thinks he can shoot up the world...The Tulsa Tribune makes no apology to the Police commissioner or to the mayor of this city for having pled with them to clean up the cess pools in this city."

The same day, the World attempted to drive a wedge between the black community by blaming “bad niggers” for the massacre. “If possible harmony between the races is to be restored these ‘bad niggers’ must be controlled by their own kind,” the editorial read.

These publications framed society’s understanding of the massacre for decades, despite the fact that Tulsa also had two black newspapers in 1921. A.J. Smitherman’s Tulsa Star was one of the flagship black publications in the state of Oklahoma and the Southwest; its presses were burned to ashes during the massacre, and Smitherman fled town as a fugitive charged with inciting a riot. The Oklahoma Sun, spun up in 1920, was a new and formidable rival to the Star; however, nearly every issue of the paper ever published has been lost, either to fire or institutional neglect of black history. What is known is that the Sun provided an invaluable public service after the massacre, publishing lists of names of people found safe in the chaotic aftermath.

It’s the white account of what happened in Tulsa that still anchors our general understanding of the massacre, in part because the infrastructure to spread black knowledge of the events was physically set aflame. The massacre was an attack on black bodies, but it was also an attack on black thought. It’s the role of modern journalists and historians to sift through the records that remain so that a more diverse set of perspectives can get us closer to the truth. And we must always remember that the first draft of history, like any other kind of writing, has its own agenda.

Thank you for reading. To learn more about the origins of Greenwood, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the community’s astonishing rebirth, check out my narrative nonfiction book Built From the Fire. The book was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and the Washington Post. Buy Built From the Fire on Amazon, Bookshop, or at your local bookseller.

Want to read more stories about neglected black history? Subscribe to Run It Back and receive articles just like this one in your inbox every other week.

Sources

Krehbiel, Randy. Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre.

“Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.” Tulsa Tribune. May 31 1921.

Parrish, Mary Jones. Events of the Tulsa Disaster. 1923

Williams, W.D. (1978). An oral history with W.D. Williams/Interviewer: Scott Ellsworth.